Evaluating the Paycheck Protection Program

Can profit maximizing firms work for the common good?

Sophia Harrison

The Small Business Administration placed financial institutions in charge of vetting and approving lending through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). The banks’ underlying goal of profit maximization raises reasonable ethical concerns over the fair distribution of these loans.

Background to the PPP

The onset of the infectious disease COVID-19 has led to large economic disruptions across the world. In the United States, COVID-19 related job loss resulted in the highest unemployment rate in nearly 100 years, reaching a peak of 14.4% in April 2020 (BLS). To combat the disastrous financial effects, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was passed in late March 2020 with the goal “To provide emergency assistance and health care response for individuals, families, and businesses affected by the 2020 coronavirus pandemic” (S.3548 CARES Act). One of the major components of the bill was the allocation of $349 billion under the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) within the jurisdiction of the Small Business Administration (SBA) with support from the Department of Treasury. Loans of up to $10 million are administered under the PPP; the loans can be fully forgiven if: i) used towards payroll, rent, mortgage interest, or utilities, ii) at least 75% of funds are used for payroll costs, and iii) all employees kept on payroll for at least 8 weeks. On June 5, 2020 President Donald Trump signed the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act to adjust criteria ii) to 60% and criteria iii) from 8 weeks to 6 months (Hare). The SBA also defines eligible small businesses for the PPP as those with less than 500 employees; meets the SBA’s industry size; has less than 500 employees per location if in the Accommodation and Foods Services; or is a sole-proprietor, independent contractor, or self-employed (85 FR 20811).

To maximize efficiency of the loan approval and distribution process, the Small Business Administration placed financial institutions in charge of vetting and approving the PPP lending (Merle). According to the SBA, all existing SBA-certified lenders qualify for the program and all federally insured depository institutions, federally insured credit unions, and Farm Credit System institutions are eligible for participation (“PPP Information Sheet Lenders”). The loans were intended to be dispersed “first-come, first-serve,” yet the actual allocation of loans was not as straight-forward (85 FR20811). After the first-round of the PPP, lenders with more than $50 billion in assets distributed 37% of all PPP loans. Specifically, large banks such as Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, PNC Bank, and Wells Fargo were among the top lenders of PPP loans (“Paycheck Protection Program Report”). It is important to note that these banks generally operate under the neoliberalist conceptions of finance as presented in Modern Finance theory. This theory draws the conclusion, from simplified assumptions, that “…rational agents aim to maximize profits” (Tan Bhala 8). The banks’ underlying goal of profit-maximization raises reasonable ethical concerns over the distribution of these loans—specifically the “first-come, first-serve” system that determines the order and amount of PPP loans.

Ethics Issues of PPP Implementation

The goal of the Paycheck Protection Program under the CARES Act is to provide benefits to small businesses affected by COVID-19. A utilitarian theory states “In all circumstances we ought to produce the greatest happiness or well-being for the greatest number,” which in the case of government-sponsored social welfare programs denotes that benefits should accrue to the targeted recipients of funds— small businesses (Tan Bhala 10). However, conflict arises when profit-maximizing institutions are placed in charge of programs for communal good. The social responsibility assigned to the establishments of power (the banks in this case) assumes they can act under “moral agency, reason, and action” to make the right choices for a large group of people. The ethical outcomes were negative because financial institutions failed to achieve the goal of helping the greatest number of small businesses. The government chose institutions driven by the goal of profit-maximization to make choices and subsequent actions that in contrast, should be aimed towards the common good. There was therefore, a conflict of goals.

Comparison to Past Disaster Relief Programs

In the past when major economic disasters occurred, such as Hurricane Katrina, government officials were directly in charge of administering loans. For example, nearly $2.6 billion worth of SBA loans were made after Hurricane Katrina in Mississippi alone (Hiramatsu and Marshall). A major difference between loans administered under Hurricane Katrina versus the PPP was many of the loans/grants administrated to small businesses under Sec. 813 after Hurricane Katrina were overseen by the SBA directly, instead of by banks (H.R.4197). Following Hurricane Katrina, the SBA distributed its staff to disaster center locations to review loan applications. However, businesses criticized the government for being inefficient and mismanaging loan applications, favoring loan applications from higher credit scores and bigger incomes, as the SBA could easily and quickly close these applications. In fact, only 60% of loans approved by the SBA reached applicants (“5 Years Later, Katrina a Tale of Failed Loans”).

There is no official reason for the SBA decision to utilize financial intermediaries during COVID-19 instead of directly working with employers. One evaluation done by the U.S. Government Accountability Office in February 2020 on disaster loans distributed from the 2017 hurricanes found the “…SBA may not be adequately prepared to respond to challenges that arise during its disaster response efforts” (“Disaster Loan Processing Was Timelier, but Planning Improvements and Pilot Program Evaluation Needed”). Perhaps the SBA desired to learn from its mistakes in past disasters and employ banks as a means of distributing funds as quickly as possible to provide immediate relief in an unprecedented economic crisis. However, it is crucial to consider the trade-off between efficiency and transparency in a time when many small businesses, and thus people, are at risk of suffering unprecedented financial losses.

Barriers to Efficiency

The wording of the PPP explicitly states that although lenders are not required to follow normal protocol that determines creditworthiness of borrowers, lenders must still abide by basic anti-money laundering policies. Such policies create asymmetric information between borrower and lender causing the lender to become more risk adverse. The lender is more cautious in processing new borrowers because it may face harsh repercussions if it chooses to lend to unreputable borrowers. The new borrowers may in fact be trustworthy customers, yet anti-money laundering policies motivate the lender to hesitate to lend to the businesses they do not have history with, hence creating a “missing,” or asymmetric information dilemma. Asymmetric information creates a barrier to efficiency by preventing many reputable new borrowers from engaging in transactions with willing lenders. In the official bill, Congress writes that “Lenders do not have to comply with SBA section 120.150” (85 FR 20811). SBA section 120.150 states “The applicant (including an Operating Company) must be creditworthy. Loans must be so sound as to reasonably assure repayment.” The section lists a nine-criteria borrower evaluation for lenders that include assessing the (d) Past earnings, projected cash flow, and future prospects and (g) “Potential long-term success” (13 CFR 120.150). Freeing lenders from following such an extensive evaluation of borrowers outlined in section 120.150 aimed to increase the speed at which the PPP loans were distributed.

Despite the disbandment of the official credit evaluation, the SBA still requires lenders to follow existing Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) protocols, intended to prevent money-laundering. Even if lending institutions are not under BSA jurisdiction, lenders must develop anti-money laundering compliance which “may include a customer identification program (CIP), which includes identifying and verifying their PPP borrowers’ identities (including e.g., date of birth, address, and taxpayer identification number), and, if that PPP borrower is a company, following any applicable beneficial ownership information collection requirements” (85 FR 20811). It is often time-costly to go through each application and verify documents provided for new customers. The consuming process of authenticating each new borrower ultimately undermines the goal of efficient and equitable loan allocation, which then undermines the objective of enabling the greatest number of small businesses to receive prompt funding, allowing them to survive COVID-19 lockdowns (Klein and Warden). The required anti-money laundering compliance increases the problem of asymmetric information: the borrowers know if their application is truthful, yet the lenders must vet each application to ensure BSA compliance. Asymmetric information has been shown to lead to pareto-inefficient (suboptimal) outcomes for both the borrower and lender, because it prevents willing economic transactions from taking place (Hernández). For example, if the threat of hefty fines from violating BSA regulations encourages lenders to take less risk in accepting new customers, banks may favor giving PPP loans to customers they already have pre-existing relationships with to minimize risks of a negative and costly outcome.

While anti-money laundering compliance forces both borrower and lender to act with moral caution and reason, we must ultimately consider the goal of the PPP: “To provide emergency assistance and health care response….” The word emergency suggests a sense of urgency for immediate aid, which the integration of anti-money laundering compliance in the PPP disregards. Ultimately, if compliance implicitly encourages banks to favor existing customers over new customers, the PPP has failed in distributing loans equitably. In an ideal situation, an economically efficient outcome would consist of all trustworthy borrowers receiving loans from lenders who in turn are able to distribute loans without apprehension about adverse consequences. When banks are not required to adhere to strict compliance laws in emergency situations, the largest amount of money can be distributed to the greatest number of small businesses given the time-sensitive nature of the lending period. As the PPP explicitly requires lenders to follow BSA protocols, banks, to minimize losses, have a stronger incentive to give loans to existing trusted customers. In fact, in early April 2020, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan faced a backlash when he stated the bank was prioritizing active borrowers over any existing or new customer (Reuters). To accomplish the objective of lending money to as many small businesses in need as possible, the PPP bill must be reformed to ease anti-money laundering conditions temporarily.

Profits v. People

Lenders

An additional conflict in the PPP bill stems from the payment of lenders, which incentivizes profit-maximizing institutions to favor giving out larger loans. Lenders are currently paid a fee per loan using the following criteria (85 FR20811):

- 5.0 percent for loans of not more than $350,000

- 3.0 percent for loans of more than $350,000 and less than $2,000,000

- 1.0 percent for loans of at least $2,000,000.

Using a simple calculation, a bank giving a loan of the maximum amount of $10,000,000 makes a commission of $100,000 versus a commission of $11,950 on the average first-round loan amount of $239,000. If most of SBA approved lenders are profit-maximizing institutions answerable to shareholders, it follows that when faced with the choice of administering a $239,000 loan or a $10,000,000 loan, the larger loan takes priority over the smaller loan.

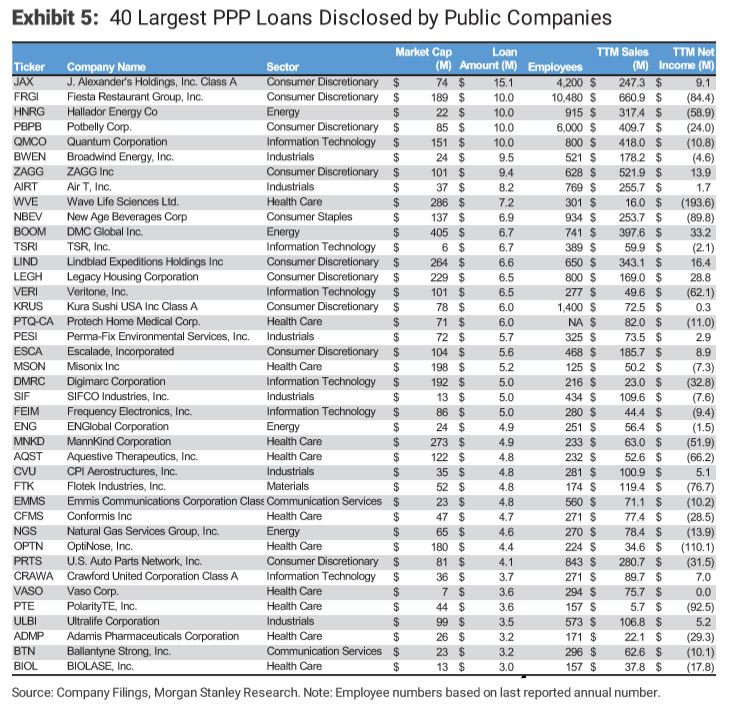

Although the PPP loans are lawfully supposed to be dispersed “first-come, first-serve,” under the threat of funding running out, profit-maximizing institutions (without regulation by a third-party) would favor larger loans to make higher commissions. The first-round of PPP loans followed this logic: large companies like Shake Shack (a $1.6 billion-dollar company with nearly 8,000 employees), LA Lakers (worth $3.7 billion), and even billionaire Jim Justice’s private companies received multi-million dollar loans under the program (Kurtzleben et al). Although these companies may qualify as “small-businesses” under the SBA industry guidelines, these companies still have access to large amounts of capital. A recent investigation by Forbes found that 71 publicly traded companies received $300 million dollars’ worth of loans, meaning that each company received, if divided equally, a $4,225,352 loan (in reality many of these public companies received the full $10 million) (Vardi). If lenders, for example, chose instead to allocate the $10 million Shake Shack loan to small businesses without as much capital, about 42 more small businesses could receive the first-round average loan amount of $239,000.

A recent PPP report released by the Department of Treasury in early July 2020 stated that Muy Brands Inc., a franchisee who owns more than 750 Wendy’s, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut restaurants received between $15-$30 million in PPP loans. The CEO James Bodenstedt of Muy Brands has given nearly $400,000 to the Trump re-election campaign so far. Despite the fact that Muy Brands Inc. owns 750 restaurants, it still fits the SBA guidelines of a “small-business” eligible for a PPP loan, because it is in the accommodation and food services industry, has more than one physical location, and employees less than 500 employees per location (85 FR 20811).

Additionally, numerous “megachurches” received multi-million-dollar PPP loans, raising ethical concerns as to whether tax-exempt organizations can fairly acquire a forgivable PPP loan funded by U.S. taxpayers. First Baptist Church in Dallas received a PPP loan between $2-$5 million, despite its official classification as a “non-exempt charitable trust,” meaning that the church is not required to pay taxes if it applies all its funds towards charitable purposes (“Treasury Names 650,000 Companies That Got U.S. Small Business Loans”). Although these companies may fit the SBA’s industry guidelines and may use the PPP funding to keep their workers on payroll, the intent of the program is to provide actual small-businesses well-needed economic relief. Smaller businesses, such as those with less than 50 employees, should have been prioritized over these larger entities—as a higher number of small businesses overall could obtain funding this way without exhausting the money originally allocated. Ultimately, working with bigger companies allows banks to earn larger profits.

Public Companies as Borrowers

The SBA defines eligible borrowers as those whose: “[c]urrent economic uncertainty makes this loan request necessary to support the ongoing operations of the Applicant” (“Paycheck Protection Program Loans FAQ”). In other words, applicants must self-evaluate whether their own financial situation deems the PPP loan necessary to continue its business. It is ethically questionable as to why publicly traded companies, such as Shake Shack who reportedly had $112 million dollars in cash at the time of application, received the full PPP loan amount of $10 million in the first-round (Vardi). The SBA has recently stated that “It is unlikely that a public company with substantial market value and access to capital markets will be able to make the required certification in good faith, and such a company should be prepared to demonstrate to SBA, upon request, the basis for its certification” (“Paycheck Protection Program Loans FAQ”). It is important to note the SBA highlights the phrase “in good faith” in their statement about PPP loans for public companies. This specific language suggests that public companies who did receive the loans, like Shake Shack, perhaps did not act “in good faith.” On April 20, 2020, Shake Shack announced it was returning its $10 million dollar loan (Chappell).

“Good faith” suggests a moral obligation on the part of the borrower to make a transparent and honest judgement to determine whether it truly needs the loan: a self-evaluation. Although most lenders favored larger PPP loan amounts which violated their moral obligations, we should also hold borrowers accountable for their behavior. PPP loans for publicly traded companies is pretty much like free money, regardless of whether the public companies verily need the money. Therefore, the misallocation of PPP funds results from both lender and borrower behavior. The PPP loans public companies received exhibit this two-way relationship of bad faith. The SBA’s assumption that both parties will act in “good faith,” even in a pandemic, may be misplaced.

Secondary Market Incentives

As PPP loans can be sold on the secondary market, banks prefer to work with bigger businesses applying for larger loans. Banks sell the larger loans on the secondary market to increase profits through larger fees. The loans may not be very attractive for those who purchase them on the secondary market, as they have a mere 1% interest rate and the responsibility of servicing the borrower is transferred to the loan buyer (85 FR 20811). A way banks overcome the low demand for PPP loans on the secondary market is by selling the loans at a discount rate (Klyce). By selling their loans to another investor, banks make money, yet sacrifice their relationship with the borrower. Once a PPP loan is sold, the responsibility of servicing the borrower is shifted to the new buyer of the loan. For the customer, this means interacting with an entirely different entity if they face issues with the repayment of their loan. The secondary market provides an opportunistic way for banks to further their profits at the expense of the customer.

New PPP Conditions

PPP loans are a non-risk purchase and as of May 2020 are fully insured by the SBA, even on the secondary market (“Paycheck Protection Program Loans FAQ”). The loans have strict terms for forgiveness: the original first-round conditions state that 75% of the loan is required to be used towards payroll costs and must be spent within 8 weeks to be fully forgiven. The conditions placed immense pressure on small businesses to spend the loan in a short period of time. In June 2020, President Trump signed the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act (PPPFA) which altered the original conditions. Among the changes: 60% (rather than 75%) of the loans are to be used towards payroll costs and the period of forgiveness is extended from 8 weeks to the end of the 2020 calendar year (Hare). The new laxer conditions may be helpful for small businesses to better allocate money while their operations are halted due to stay-at-home orders. Yet, the small businesses that need the immediate funding to pay their rent are most likely still waiting their turn to receive an initial PPP loan.

Agents

The agent commission system may place less profitable small businesses at a disadvantage. Agents (consultants, accountants, lawyers) who help the borrower secure the loan are paid using the following criteria (85 FR 20811).

- 1.0 percent for loans of not more than $350,000

- 0.50 percent for loans of more than $350,000 and less than $2 million

- 0.25 percent for loans of at least $2 million.

If Agent A has a chance to receive a $5,000 commission on a $2 million-dollar loan versus a $3,500 commission on a $350,000 loan, Agent A may want to work with larger companies who can apply for a higher loan amount. Furthermore, small businesses may not have access to the initial capital needed to hire the agents. Agents can help make the process of applying for loans more streamlined and can utilize pre-existing relationships and connections with approved lenders to help clients.

Disproportionate Effects on Minority-Owned Small Businesses

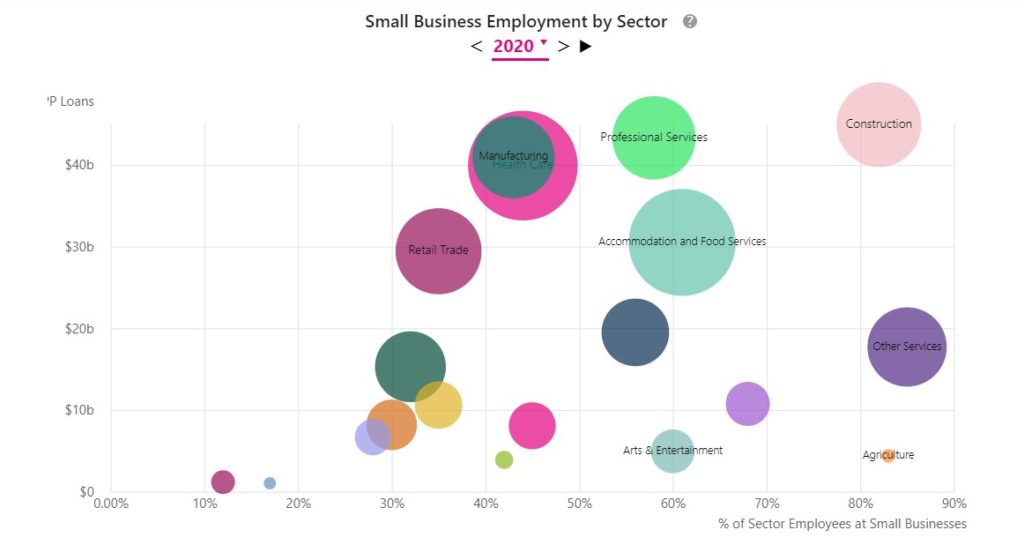

A recent survey of entrepreneurs completed by McKinsey & Company found that the sector of small businesses most affected by COVID-19 contain the highest share of minority-owned small businesses. These businesses include accommodation and food services, personal and laundry services, and retail (Dua et al). Another report finds that “Fifteen percent of establishments in the regions most affected by declines in hours worked and business shutdowns received PPP funding; in contrast, thirty percent of all establishments received PPP funding in the least affected regions” (Granja et al.). If we are to maximize the social good, then the small business sectors with the highest number of employees affected should receive the most funding. This desirable outcome was not a reality in the first-round. Considering that the accommodation and food services industries were among the most impacted, they still received $15 billion less in PPP loans than the construction sector, which employs nearly 3 million less people. Perhaps most disheartening, the personal care (other) services sector received less than $25.6 billion less in PPP dollars than professional services, despite having roughly equal the number of employees in the small businesses (“Five Things the Data Says about the COVID-19 Pandemic”). Congress needs to comprehend the limitations of placing profit-maximizing institutions in charge of distributing vital aid in a pandemic. In fact, the PPP loan distribution in its present form contributes to increasing socioeconomic inequality in the United States today.

With public outcry over the death of George Floyd and the response statements quickly released by many big banks, these institutions must reform internally on how they handle the loan application process. Words are not enough; banks need to act decisively on this issue. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta and Cleveland found that “Firms owned by African-Americans were 20% less likely to obtain financing at large banks than white-owned businesses with similar profitability, credit risk and other factors” (Simon and Rudegeair). These discriminatory practices can often create negative experiences for customers regarding the financial system. Discrimination not only undermines the perceived trustworthiness of financial institutions, but also compromises the public perception of the U.S. government’s competency to conduct programs for the communal good. A study by economic researchers, Nathan Nunn and Leonard Wantchekon found that levels of current trust are directly associated with levels of past treatment from those with power (Nunn and Wantchekon). Trust, specifically social trust (trust in others to act with virtue), was shown to directly affect factors such as schooling and rule of law, which ultimately affects levels of economic performance (Bjornskov). The unethical lending practices of banks may ultimately lead to both widening racial disparities and decreasing levels of trust towards institutions.

Moving Forward

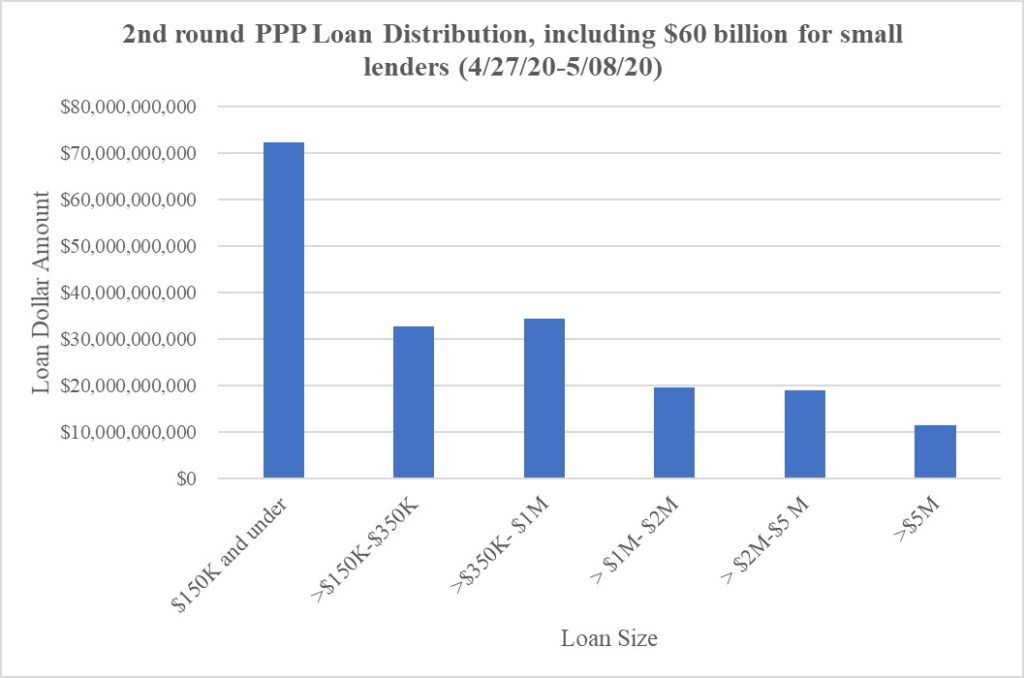

A second-round of PPP funding ($310 billion) was dispersed in late April; the deadline to apply for a second-round PPP loan has been extended to August 8, 2020 (Snel). $60 billion of the second-round funding was reserved for smaller lenders, such as small insured depositary institutions, credit unions, community financial institutions. Of the $60 billion, $30 billion was set aside for lenders with assets less than $10 billion, and the second $30 billion for those with assets between $10 billion and $50 billion. In early May 2020 the SBA reported that in the second-round, institutions with less than $10 billion in assets approved $59,970,117,870 worth of loans, while those with more than $10 billion but less than $50 billion in assets approved $28,943,084,497 worth of loans. Small lenders represent more than 47% of the loans approved, yet banks with $50 billion or more in assets still constitute the other 53% (“Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report: Second Round”). The SBA has not made the breakdown of institution approved dollar amount publicly available for the first-round.

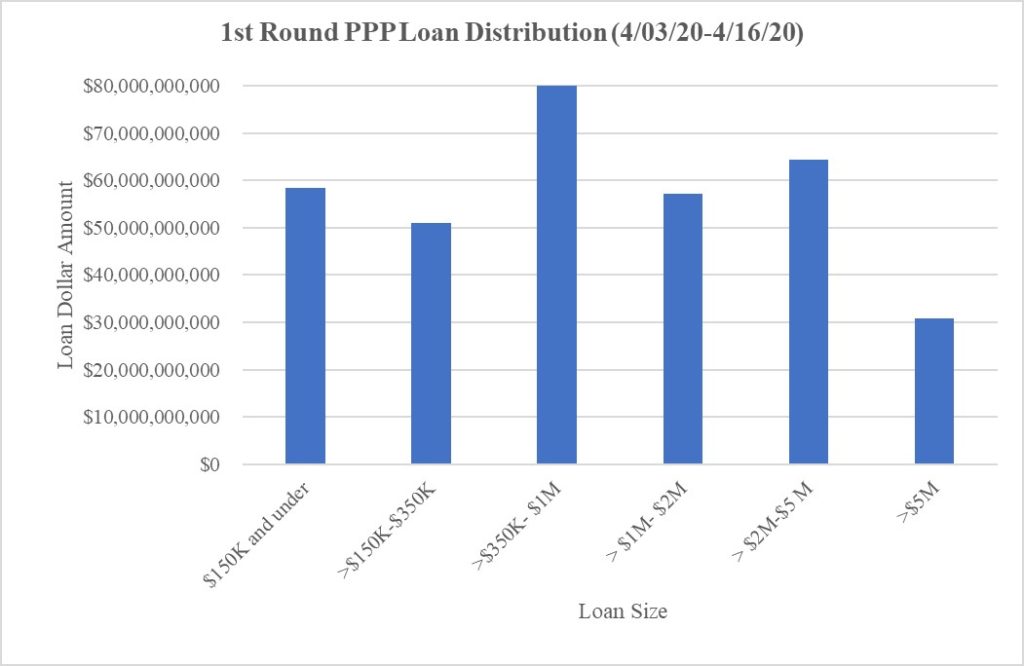

As of June 27, 2020, $134,453,990,454 of funds remain out of the $310 billion allocated in the second-round—a sizeable amount considering the first-round ran out in two weeks (“Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report”). The $60 billion set aside for small lenders in the second-round may have increased the number of PPP loan to smaller, less profitable businesses (banks with less than $1 billion in assets tend to issue an average loan size of $58,000 versus banks with over $50 billion in assets with average a loan amount of about $90,000) (Kurtzleban). In addition, the SBA has announced it will audit loans made in the second-round that are over $2 million dollars (“Payment Protection Program Loans FAQ”). Waiting until the second-round to make such an important change to the PPP places small businesses at a major disadvantage (see Figures 2, 3). In the first-round of the PPP, the banks in charge of the program did not appear to prioritize small businesses most impacted by the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders.

Banks need to be more transparent with the loan decision-making process. Not only must there be bank reform in the handling of PPP loans, but the Paycheck Protection Program itself must be improved to explicitly regulate these institutions and prohibit any unnecessary exploitation of the loan distribution process. In the future, PPP funding should place an emphasis on staggering the opening of loan applications according to small business employee number. This system would ensure funds are not disproportionately given to larger businesses, while allowing smaller businesses (who on average receive smaller loan amounts) to apply first and receive guaranteed funding. The refined loan distribution system would decrease the negative externalities related to widening socioeconomic inequality, as well as improve the general levels of trust in government-sponsored relief programs.

Example of Employee Number-Based Staggering of Loan Applications:

*any small business that applies must ensure that the PPP loan is necessary for their expenses

- Week 1: Small businesses that have fewer than 30 employees apply for loans.

- Week 2: Small businesses that have fewer than 50 employees apply.

- Week 3: Small businesses that have fewer than 100 employees apply.

- Week 4: Small businesses that have fewer than 500 employees apply.

Policymakers should consider the financial ethics implications before policy is implemented. Any government sponsored aid program should not encourage or be blind to unfair behavior by financial institutions, especially when livelihoods are at risk.

*Note the differences in loan size distributions between the Figure 3 (1st round without the amendment for new borrowers) vs. Figure 4 (2nd round after the SBA faced major scrutiny/ with the $60 billion allocated for small lenders). In Figure 3 (Round 1), small businesses that receive a loan size of $350K-$1M receive the most dollar amount, whereas in Figure 4 (Round 2), small businesses that receive a loan size of $150K and under receive the most dollar amount.

Works Cited

Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How does social trust lead to economic growth? Southern Economic Journal, 78, 1346–1368.

“Business Loan Program Temporary Changes; Paycheck Protection Program,” 85 Federal Register 20811 (15 April 2020), pp. 22381-22383.

Chappell, Bill. “Shake Shack Returns $10 Million Loan To U.S. Program For Small Businesses.” NPR, NPR, 20 Apr. 2020, www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/20/838439215/shake-shack-returns-10-million-loan-to-u-s-program-for-small-businesses.

“Disaster Loan Processing Was Timelier, but Planning Improvements and Pilot Program Evaluation Needed.” Report to Congressional Committees, GAO, Feb. 2020, www.gao.gov/assets/710/704409.pdf.

Dua Andre, et al. “Effect on Minority-Owned Small Businesses in the United States.” McKinsey & Company, 2020, www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/covid-19s-effect-on-minority-owned-small-businesses-in-the-united-states#.

Granja, Joao, Christos Makridis, Constantine Yannelis, and Eric Zwick, “Did the Paycheck

Protection Program Hit the Target?,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, 2020.

Hare, Neil. “Trump Signs New Law Relaxing PPP Rules: What You Need To Know.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 5 June 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/allbusiness/2020/06/05/trump-signs-new-law-relaxing-ppp-rules-what-you-need-to-know/#340ba25b31e3.

Hernández, René A. “Stylised features of Asymmetric Information, Pareto Inefficiencies and Incomplete Markets.” (2003)

Hiramatsu, T., & Marshall, M. I. (2018). The Long-Term Impact of Disaster Loans: The Case of Small Businesses after Hurricane Katrina. Sustainability, 10(7).

H.R.4197 – Hurricane Katrina Recovery, Reclamation, Restoration, Reconstruction and Reunion Act of 2005, vol. 1, 2005. www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/4197/text.

“Five Things the Data Says about the COVID-19 Pandemic.” USAFacts, USAFacts, 7 June 2020, usafacts.org/articles/covid-19-impact-jobs-health-state-finances/.

Klein, Aaron, and Staci Warden. “Anti-Money Laundering Rules: An Emergency Assistance Roadblock.” Brookings, Brookings Institution, 8 Apr. 2020, www.brookings.edu/opinions/anti-money-laundering-rules-an-emergency-assistance-roadblock/.

Klyce, John. “Memphis Investor: PPP Changes Could Make Loans Less Attractive for Banks, Secondary Market.” Small Business Resource Guide, Memphis Business Journal, 8 June 2020, www.bizjournals.com/memphis/news/2020/06/08/ppp-changes-are-great-for-busiensse.html?ana=RSS&s=article_search.

Kurtzleben, Danielle. “Not-So-Small Businesses Continue To Benefit From PPP Loans.” NPR, NPR, 4 May 2020, www.npr.org/2020/05/04/850177240/not-so-small-businesses-continue-to-benefit-from-ppp-loans.

Kurtzleben, Danielle, et al. “Here’s How The Small Business Loan Program Went Wrong In Just 4 Weeks.” NPR, NPR, 4 May 2020, www.npr.org/2020/05/04/848389343/how-did-the-small-business-loan-program-have-so-many-problems-in-just-4-weeks.

Merle, Renae, and Aaron Gregg. “Big Banks Took ‘Free Money’ in 2008. They’re Turning Their Backs Now on Small Businesses, SBA Official Says.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 8 Apr. 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/08/video-sba-official-blasts-big-banks-over-failure-quickly-distribute-loans/.

Nunn, N., and Wantchekon, L. (2011), “The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa,” American Economic Review, 101, 3221–3252.

Packin, Nizan Geslevich. “We Need Ethical Banking In The Era Of COVID-19.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 28 Apr. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/nizangpackin/2020/04/25/we-need-ethical-banking-in-the-era-of-covid-19/.

“Paycheck Protection Program Loans FAQ.” United States Department of Treasury and the Small Business Administration, 2020. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Paycheck-Protection-Program-Frequently-Asked-Questions.pdf

“Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Information Sheet Lenders.” PPP Lender Information Sheet, United States Department of Treasury, 2020, home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/PPP%20Lender%20Information%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf.

Reuters. “Bank of America Slammed over Favoring Small Biz Loans for Existing Customers.” New York Post, New York Post, 3 Apr. 2020, nypost.com/2020/04/03/bank-of-america-slammed-over-favoring-small-biz-loans-for-existing-customers/.

S.3548 CARES Act, vol. 1, 2020. www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3548/text.

Simon, Ruth, and Peter Rudegeair. “Big Banks Favor Certain Customers in $350 Billion Small-Business Loan Program.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 6 Apr. 2020, www.wsj.com/articles/big-banks-favor-certain-customers-in-350-billion-small-business-loan-program-11586174401.

“Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program.” Coronavirus Response, Wells Fargo, 2020, update.wf.com/coronavirus/paycheckprotectionprogram/.

Snel, Ross. “Congress Votes to Extend PPP to Aug. 8.” Barron’s, Barrons, 2 July 2020, www.barrons.com/articles/congress-votes-to-extend-ppp-to-aug-8-51593705096.

Tan Bhala, K. (2019). “The philosophical foundations of financial ethics”. In Research Handbook on Law and Ethics in Banking and Finance, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784716547.00009

“Treasury Names 650,000 Companies That Got U.S. Small Business Loans.” CBS News, CBS Interactive, July 2020, www.cbsnews.com/news/ppp-loan-recipients-treasury-names-small-businesses-receiving-funds/.

Vardi, Nathan. “71 Publicly Traded Companies Got Paycheck Protection Funding Before Money Ran Out.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 20 Apr. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/nathanvardi/2020/04/20/seventy-one-publicly-traded-companies-got-paycheck-protection-funding-before-money-ran-out/#6b19645c5087.

Vazquez, Maegan. “Restauranteurs Plead with Trump to Make PPP Loan Changes.” CNN, Cable News Network, 18 May 2020, www.cnn.com/2020/05/18/politics/donald-trump-restaurants-coronavirus/index.html.

United States, Congress. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report, SBA, 27 June 2020. www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/PPP_Report_Public_200627%20FInal-508.pdf.

United States, Congress. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report: Second Round, SBA, 27 June 2020. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/PPP_Report_200508_0-508.pdf

“5 Years Later, Katrina a Tale of Failed Loans.” CBS News, CBS Interactive, 24 Aug. 2010, www.cbsnews.com/news/5-years-later-katrina-a-tale-of-failed-loans/.

Umbrella Image courtesy of Nonprofit Attorneys