Ethics of Universal Basic Income

By: Victoria Tse

Part 1 of SPI’s Universal Basic Income Series

What is a Universal Basic Income (UBI)?

A basic income is a universal income grant available to every citizen without means test or work requirement. How much money governments should issue to their people is still a topic of discussion within countries looking to launch UBI experiments. Switzerland was the first to hold a public referendum introducing the UBI with the Federal Council approving a ballot issuing adults $2,500 and children $625 a month. The referendum failed – this time. Proponents of the UBI claim that having a guaranteed basic income would especially benefit the poor working class where working 40 hours a day with perhaps two jobs instead of one, might not be enough to cover basic living expenses and needs. Theoretically, the UBI would alleviate abject poverty and redistribute wealth in doing so. A concerning feature of a guaranteed basic income is the greater level of autonomy recipients would have if free to spend government issued money. Another concern with increased autonomy is the elimination of the incentive to work or to exceed job expectations. This same level of autonomy cannot be found in current welfare systems where money is issued paternalistically and restrictively as there are set amounts allocated to only certain items of goods.

A Brief Introduction to a Universal Basic Income

The “free money” ideal behind the universal basic income is as radical as it is attractive. The universal basic income is a more cost efficient replacement for current welfare systems as a method of alleviating poverty. Swiss and Finnish governments have recently launched basic income experiments, but the U.S. government has yet to follow in the footsteps of its European counterparts. Canada and Spain have also demonstrated interest in the UBI and are looking to initiate upcoming trials.

The universal basic income proposal is reminiscent of liberal economist, Milton Friedman’s negative income tax through which individuals earning below a certain threshold receive money from the government rather than pay taxes. The basic income differs from the negative income tax in that the latter is unconditional and universal whereas the former is exclusionary. With universal basic income, the government issues money without strings attached leaving individuals to spend it in any way they see fit. The money is issued to individuals of all social classes and everyone receives the same amount irrespective of income bracket. The unconditionality of a UBI circumvents the “poverty trap”, a phenomenon in which people who receive conditional benefits have no incentive to take lower-paying jobs because their wages will be offset by a matching reduction in benefits. The basic income alleviates the consequences of the welfare trap in current welfare systems where those who live below the poverty line are ineligible for government aid because they are a dollar over the cutoff point.

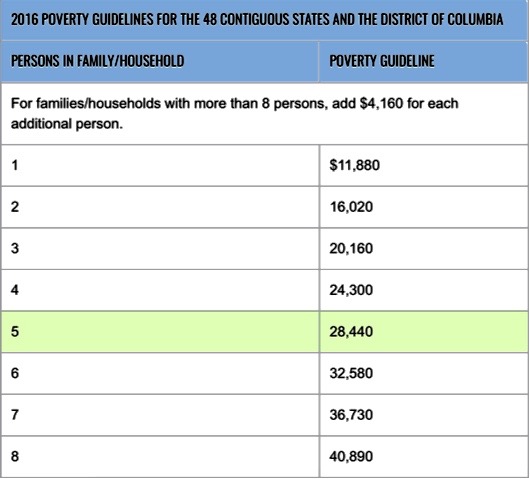

Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines for 2016

Thus far, we have outlined the basic principles of the UBI and the goals economists and politicians have in mind with implementation. A universal basic income is designed to combat the increasing loss of jobs to artificial intelligence advancements and to redistribute wealth in the process. The utilitarian and consequentialist approach along with Kantian ethics warrant the granting of basic income to individuals as a distinctive legal rights status, although their methods of arriving at the conclusion that a UBI is morally permissible are different.

The Ethics Of Universal Basic Income

In analyzing the moral implications of such a radical notion, we apply a variety of philosophical proofs to arrive at conclusions supporting the implementation of a guaranteed basic income based on the ethical values the UBI proposes. We begin with utilitarian and consequentialist theories and end with Kantian ethics in arguing for the moral permissibility of UBI.

Utilitarian Analysis

Utilitarianism is a normative ethical theory that proposes actions are right, if and only if, they promote happiness and maximize pleasure, even if those actions in question cause suffering and impinge upon the natural rights of a few. The harm brought to a smaller number of people in attaining the maximum fulfillment of satisfactions is justified insofar as what is gained compensates for what is lost. Similar to consequentialism where the ethical value of an action is judged by the consequences it produces, utilitarianism only examines effects of actions and is less concerned with the intent of an action (good or bad). The theory of utilitarianism is often criticized for its vulnerability to expediency where universally unjust actions (lying, stealing, murdering) are permitted if their consequences are foreseeably positive. In utilitarian theory, wrong actions are those, which produce pain, unhappiness, or displeasure. A utilitarian analysis of a UBI is as follows:

- We ought to maximize utility.

- A UBI would maximize utility.

- Therefore, we ought to have an UBI.

Utility in this sense refers to the pursuit of happiness and the mitigation of unhappiness. In answering the question of what things are good, classical utilitarians, Bentham and Mill, adopt a hedonistic approach in which the only thing good in itself is happiness. Happiness is intrinsically valuable and it ought to be within every person’s interest to maximize pleasure, fulfilling what Mills calls the “greatest happiness principle”. In utilitarianism, every individual’s right to happiness and her interests are considered equally. This equal consideration of interests is consistent with the unconditionality of the basic income in which an income bracket neither qualifies nor disqualifies an individual from receiving the same amount of money from another individual whose income bracket or economic and social hierarchy is different.

Next, we examine the extent to which UBI maximizes utility and in what ways it promotes happiness. A basic income fosters social solidarity and alleviates poverty through the redistribution of wealth, although such multiplications of well-being might violate individual rights as money is redistributed from the rich to the poor. A utilitarian approach however permits infringing the rights of a few if the act yields happiness for the majority.

Another way in which a basic income maximizes happiness without violating rights of others is the knowledge and sense of security it gives to those who find themselves displaced from a job. Based on what utilitarians consider to be wrong actions, being unemployed and without the capacity to sustain oneself produces unhappiness and displeasure as one’s basic securities and needs are threatened. Thereby, a guaranteed basic income would not only offset the negative consequences of job loss, but is morally permissible on the grounds it maximizes utility.

Ethical Egoism

Egoism is another normative ethical principle proposing moral agents ought to act in accordance with their self-interests. For this article, we focus on normative egoism, under which both ethical and rational egoism are relevant. Contrary to altruism where an individual’s moral obligation lies in service of others even to the extent of sacrificing her own well-being and interests, ethical egoism proposes an individual’s only moral duty is the promotion of self-interests above the interests of others.

Selfish acts are morally permissible because “selfishness is a proper virtue to pursue” as argued by philosopher Ayn Rand. Rational egoism insinuates that acting against one’s self interests is irrational, while acting in accordance with one’s self interests is to act within reason and to be perfectly rational (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). To apply ethical egoism to UBI, it is necessary to first consider our self-interests.

- I am benefited by the elimination of poverty.

- A UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty.

- I ought to pursue what benefits me.

- Therefore, I ought to pursue a UBI.

Ethical egoism assumes it is within our interests to have a supplementary income as well as something we can rely on should we find ourselves jobless. Therefore, we can identify the eradication of poverty as something within our self-interests because of the benefits having basic needs met by a monthly check if we are temporarily unemployed. It is important to note here the status of unemployment is not the only qualification for the UBI to be beneficial. Individuals who are still employed or well-off still benefit from money supplementing primary income. Therefore, it is irrational not to pursue a program designed to eliminate poverty.

A common counter argument to ethical egosim is its inconsistency. How can everyone pursue self-interests assuming all these interests are identical and universal? This position poses a problem in naturally competitive situations, but does not apply to the basic income because a UBI is not dependent on sociological presumptions that indicate need or merit. In this case, one individual’s entitlement to a monthly check does not disqualify or hinder to any extent, another individual’s entitlement to the same monthly check given the UBI’s unconditionality.

Premise 2 here, a UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty, is a necessary assumption for the ethical egoism argument. This also is one of the more debatable parts of whether UBI should be implemented because it has not yet been proven that a UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty. There are many compelling arguments in support of and also against the poverty proposition, which I will discuss shortly.

Consequentialist Analysis- Foreseeable Consequences vs. Actual Consequences

Consequentialism is closely associated with utilitarianism, as both determine an action’s moral value based on the consequences it yields. A consequence in the sense of consequentialism refers to the action and the outcome brought about by this action. An “action” is taken to be anything done deliberately and with intention, and not as things beyond our control such as bodily functions like blinking or sneezing, which are unintentional. Intentional actions by consequentialist definition are actions done with the intended outcome of achieving some end. For example, my intention in flicking a light switch off is to turn off the lights, which is an end. When using consequences to assess what should be done or what should not be done, we perform our assessment on the basis of the best available evidence at that time. Our best available evidence for a UBI assessment are the trials and experiments already performed or are currently in progress such as those activated in Switzerland and Finland.

There are many types of consequentialism, but we focus on Plain Consequentialism, which can be used to address the issue with Premise 2 in the previous ethical egoism argument. Plain Consequentialism is a theory dictating only one action of all the possible actions an individual can take is right or is better insofar as its consequences yield more pleasure or happiness than the other consequences. If action A’s consequences are better than consequences of action B, then action A is of higher moral value than B. So if your action does vastly more good than what most other people would do in similar circumstances, but you could have chosen an action that would have done even a little more, Plain Consequentialism says that what you did was morally wrong (IEP). In applying this proposition to our previous premise that UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty, this claim can only be justified insofar as our current welfare systems yield less pleasure than a guaranteed basic income. With plain consequentialism, we may conclude that not choosing to implement a UBI, assuming it’s consequences would maximize a greater amount of happiness than other welfare systems, is morally wrong.

In analyzing the moral permissibility of a UBI, it is critical to contemplate questions regarding what sort of foreseeable consequences count as good consequences and who are the primary beneficiaries of UBI. To make such an assessment, we must focus on foreseeable consequences rather than actual or hindsight consequences. An action of foreseeable consequence is morally right, if and only if, “its expected value is at least as great as the expected value of alternative actions” (Strasser). In other words, the action is morally right if it is assessed to be the best overall action to take in the avoidance of negative consequences. Probable consequences of a UBI might include a decrease in work incentive as dependency on the guarantee of a basic income grows, or even worse is the possibility that people might quit their jobs altogether if they find that a UBI supports a satisfactory standard of living. This possibility introduces another more obvious moral issue, which is permitting able-bodied individuals to live off public transfers without having to contribute in any way.

Fiscal Realities

Another foreseeable consequence is the inability of countries to fund UBI. A UBI may be economically infeasible if countries cannot afford the program without high taxation rates. The latter may consequently act as disincentives to work and entrepreneurship. President Robert Greenstein of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities argues that a UBI may more likely increase poverty than reduce it based on the analysis of what it would cost and where funding for such a large welfare system would originate. Greenstein demonstrates the following cost analysis of UBI in the U.S:

“There are over 300 million Americans today. Suppose UBI provided everyone with $10,000 a year. That would cost more than $3 trillion a year — and $30 trillion to $40 trillion over ten years.

This single-year figure equals more than three-fourths of the entire yearly federal budget — and double the entire budget outside Social Security, Medicare, defense, and interest payments. It’s also equal to close to 100 percent of all tax revenue the federal government collects.

Or, consider UBI that gives everyone $5,000 a year. That would provide income equal to about two-fifths of the poverty line for an individual (which is a projected $12,700 in 2016) and less than the poverty line for a family of four ($24,800). But it would cost as much as the entire federal budget outside Social Security, Medicare, defense, and interest payments” (cbpp.org).

Perhaps the United States has yet to welcome the idea of a UBI with the same optimism put forth by Switzerland and Finland because a UBI “financed primarily by tax increases would require the American people to accept a level of taxation that vastly exceeds anything in U.S. history”. Considering there will be increases in expenses directed towards investment in areas to “help keep Social Security and Medicare solvent and avoid large benefit cuts in them”, Greenstein projects that a UBI in the U.S. would not advance very far (CBPP.org).

In framing the question of affordability, UBI proponents like economist and professor, Ed Dolan, propose we finance UBI by eliminating “all means-tested programs outside health care” which includes Pell Grants that help low-income students afford college, free school lunches, Head Start which promotes school readiness for children under 5 from low income families, refundable tax credits, SNAP (food stamps), SSI, etc. Only by eliminating these existing programs can every individual expect to receive an annual UBI of $1,582, a level of support well below the average of what most low income families now receive. Dolan also notes this number can be elevated to a projected “$4,452 per person, or $17,800 for a family of four, which is about 75 percent of the official poverty income for such a family”, if and only if policymakers are willing to eliminate what he calls “middle class tax expenditures” referring to all tax benefits for 401 (k)s, the mortgage interest deductions, IRAs, and other retirement savings. However, the chances of policymakers eliminating the aforementioned are nil. Dolan’s theoretical proposal of funding a UBI through the elimination of existing means-tested welfare programs and middle-class tax expenditures favors families and individuals who fall below the official poverty guidelines given that in his plan, they would be the primary beneficiaries of UBI. However, Greenstein’s analysis differs in that taking the dollars targeted on people in the bottom fifth or two-fifths of the population and converting them into universal payments for people on the highest rung of the income scale would be redistributing income upward, which is inconsistent with the UBI’s goal of alleviating poverty. In this sense, UBI might exacerbate poverty depending on who analyzes its foreseeable consequences and how the data are interpreted. We have yet to know actual consequences until the program is implemented in its entirety. Therefore, it is debatable whether a UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty and if it can be done, at what risks and cost.

Consequentialism and utilitarianism often come under scrutiny for their leniency in what is morally permissible. Under both frameworks, inherently wrong acts (lying, stealing, murdering, cheating) would be permissible if they maximize pleasure. To illustrate, a consequentialist would think it morally permissible and justified to kill 1 person, if in the act of killing one, 10 people are saved. Non-consequentialists, however, disagree and instead argue killing is intrinsically wrong. Therefore, consequences should not be used to draw exceptions in certain cases. We can think of consequentialist theory as focusing on outputs whereas non-consequentialist approaches like Kantian ethics are input driven.

Non-consequentialist Approach: Kantian Ethics

Kant’s moral philosophy does not examine consequences to determine an action’s ethical value, but rather places significance on compliance with duties. The Categorical Imperative (CI) prescribes a standard of rationality to which all moral and rational agents are held. This is the standard to which we hold ourselves when we evaluate our actions (judge them to be right or wrong). We deem this the law of freedom because as individuals we are free to meet standards of morality or fall short of them.

The concept of duty is essential to moral decision-making and without a clear conception of the obligations to which we are bound, we cannot proceed to make an informed decision about what we ought to do. Duties in Kantian ethics are articulated as “oughts”, so we can think of them as imperatives or commands. There are two types of imperatives, the hypothetical and categorical, the former of which is only necessary to follow if we desire some end while the latter is not qualified by such an if-clause. For example, a hypothetical imperative (HI) looks like this: “If you want X, then do/don’t do why”. Our duty in the HI is context-specific and contingent upon us wanting to achieve some end, so we are thereby technically not bound to follow rules if we don’t want to attain a certain end. It would be feasible to dismiss our moral obligations and duties simply by declaring that we don’t want to pursue X, so we are not going to follow rules.

Because following the HI is conditional on the desire to achieve an end, Kant says we only are obligated to act on the Categorical Imperative since following its command is necessary, irrespective of our desires. Categorically, our duties would sound like this: ‘Don’t lie’, ‘Don’t commit murder’, ‘Help others’. Such moral duties command universality and absolute necessity, and are independent of outcomes we want to attain. To derive our moral obligations and duties, we turn to deontology, which tells that right actions are those that conform to moral norms.

In the social application of Kantian ethics, we utilize the principle of the “Kingdom of Ends”, which informs us of three things: 1) things we must do, 2) things we are allowed to do, 3) things we must never do. The question now becomes how do we find out what we ought to do. To determine this, we must perform a thought experiment where the only actions we are permitted to act on are ones in which we can coherently will that our maxim, or rule, become universal law. In other words, imagine a world in which everyone followed the same maxim you are thinking of following. If it leads to a contradiction, it is concluded the action is immoral. To illustrate this thought, we will use the UBI as an example. The redistribution of wealth benefits the poor at the cost of those whose wealth is extracted from as the source of redistribution. According to Kantian ethics, “stealing from the rich” to benefit the poor is a violation of individual rights and is morally impermissible because stealing can never be made acceptable on the basis that if everyone followed this maxim, it would make the action of stealing impossible.

Kantian ethics also dictates human beings should be treated as “ends in themselves”, which has a number of meanings. Humans are deserving of respect, irrespective of what they have done or are about to do. Thus, we are not permitted to violate another person’s dignity and we ought to make the ends of others our own. Taking into consideration this approach, we can derive the following:

- We should always treat other persons as ends in themselves, never merely as a means to an end and respect their human dignity.

- A society that allows people to go poor, violates their human dignity.

- A UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty.

- So, we ought to have a UBI.

In describing a UBI as the best way to eliminate poverty, Premise 3 presupposes that a UBI would be better or more efficacious at eliminating poverty than current welfare systems. The legitimacy of Premise 3 here is dependent on a consequentialist analysis of UBI. As mentioned before, the claim that “a UBI is the best way to eliminate poverty” is debatable depending on the analysis of its foreseeable consequences. Since we have limited knowledge regarding its actual consequences, the next best resource to draw from are foreseeable consequences mapped out by economists and policymakers. According to Charles Murray of the Wall Street Journal, “as of 2014, the annual cost of a UBI would have been about $200 billion cheaper than the current system. By 2020, it would be nearly a trillion dollars cheaper”. If it can be implemented, a UBI would be more simple than the current welfare system given the “U.S. spends about $1 trillion annually on safety net programs and the federal government alone has over 100 different means-tested programs”. Transitioning to a UBI would eliminate the scattering of these means-tested programs and “all that is really needed is a list of everybody in the country who is eligible and a bank account or debit card to receive the money” (forbes.com). Dolan notes if we were to replace all means-tested programs and the current welfare system with a UBI, this “would sharply decrease marginal effective tax rates for poor and near-poor families, thereby providing enhanced work incentives”.

Another way to consider the moral permissibility of a UBI is through our duties of beneficence (helping others) and duties of perfection (cultivating one’s talents). If we are bound by obligation to help others and to also cultivate our own talents, then it is immoral for us to act against these duties. A UBI fulfills both of these duties independently; duties of beneficence comply with premise 2 which, states we should act to eliminate poverty if we have the means to do so. Duties of perfection may be fulfilled by a UBI because eliminating the pressure to work allows more time for an individual to cultivate her talents, if she chooses to spend time investing in herself.

Conclusion

The universal basic income has conceivably gained political traction chiefly because of its appealing potential to address the shortcomings of the current welfare state, but the questions of where funds for the program come from, who benefits and who loses are still being answered in experiments. It is challenging to assess the moral permissibility of an action where the consequences have yet to materialize, forcing us to apply foreseeable consequences that may differ considerably from actual consequences. It appears that a UBI might work in Western Europe, but its outlook in the U.S. is not nearly as plausible. Until all possible pitfalls of a UBI are addressed, countries and policymakers should not be eager to jump the gun and replace all means-tested aid with something universal. Special attention should be paid to the funding a UBI that is affordable without the raising marginal tax rates excessively. Some key philosophical approaches suggest a UBI, if possible to implement, would be morally permissible, depending on further empirical data.

-xxx-

Sources

“Commentary: Universal Basic Income May Sound Attractive But, If It Occurred, Would Likelier Increase Poverty Than Reduce It.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 July 2016.

David Pakman Show. “Basic Income: Finland to give everyone $870/month, Eliminate Welfare”. Online Video Clip. Youtube.com, Dec. 9 2015

“EconoMonitor : Ed Dolan’s Econ Blog » Could We Afford a Universal Basic Income? (Part 2 of a Series).” Ed Dolans Econ Blog RSS 092. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 July 2016.

“Ethics Guide- Consequentialism.” Bbc.co.uk. BBC, n.d. Web. 22 June 2016.

Flowers, Andrew. “What Would Happen If We Just Gave People Money?” FiveThirtyEight. N.p., 2016. Web. 22 June 2016.

“Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 June 2016.

Kant, Immanuel, and Mary J. Gregor. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge UP, 1998. Print.

Mill, John Stuart, and George Sher. Utilitarianism. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 1979. Print.

Murray, Charles. “A Guaranteed Income for Every American.” WSJ. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 July 2016.

“Poverty Guidelines.” ASPE. N.p., 2015. Web. 08 July 2016

Strasser, Mark. “ACTUAL VERSUS PROBABLE UTILITARIANISM.” The Southern Journal of Philosophy 27.4 (2010): 585-97. Web. 22 June 2016.

“What Is Basic Income? | BIEN.” BIEN. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 June 2016.