Ethics Study: Silicon Valley Housing Crisis

By: Sophia Harrison

1. Introduction

The Silicon Valley housing crisis requires more than public relations philanthropy by Silicon Valley technology companies. While the billion-dollar donations may bolster public opinion of Apple, Google, and Facebook, they are unlikely to fully fix the problem. As these tech companies are profit-driven, they are likely primarily driven by self-interest. This concept is evident in their affordable housing plans where their billion dollar “donations” resemble investments rather than pure altruism. While philanthropy may be temporarily beneficial, we must establish a more comprehensive plan to alleviate the crisis: enacting legislation (changing zoning laws) and increasing education (reforming NIMBY-ism). Tech companies must also commit to making conscious decisions to incorporate ethics into their practices by taking moral responsibility to improve the social good in the area where they build their wealth.

Silicon Valley’s affordable housing crisis can be used as a guiding example for future cities to maximize the social good through smart regulation of the private sector. The Silicon Valley housing plight calls for an internal reform of corporations to commit to integrating a set of ethical principles before moving to high-density areas—values such as transparency, integrity, and dedication to the social good. The pledge to these ethical responsibilities will create a more equitable society by reducing large wealth inequalities, ultimately bettering the quality of life for the greatest number of residents.

2. Background to Silicon Valley

Many consider Silicon Valley in Northern California, the “perfect” place to live: sunny weather no matter the season, proximity to the beach and giant Redwood forests, and the center of technological innovation. Contrary to these positives, Silicon Valley is also home to a hidden problem: in 2019 there were approximately 9,706 homeless people, a 31% increase from 2017. Of the 9,706 people, 30% cited job loss as a top reason for homelessness and nearly 66% could not afford rent for permanent housing in the area (“2019 Silicon Valley Index”). In an area where the median cost of rent is nearly double the national median cost of rent (in Silicon Valley the median monthly rent is $3,028 versus the monthly U.S. median is $1,661), it is not surprising working and middle-class people are continually priced out of the housing market (“Median Rental Rates”).

Silicon Valley consists of Santa Clara County: major cities include Sunnyvale, Cupertino, San Jose, Santa Clara, Mountain View and San Mateo County: Palo Alto, Menlo Park, Redwood City, and Atherton. In total, Silicon Valley is home to approximately 4 million people. Silicon Valley was inhabited by the Ohlone peoples before the arrival of the Spanish in the late 1700s. In the late 20th century, Silicon Valley was a flourishing agricultural area, where fruit was produced. Frederick E. Terman pioneered the culture of innovation in the Valley through increasing radio and communications research, as well as promoting the developments of “start-ups” by students such as Hewlett and David Packard (founders of computer company Hewlett Packard). Major migration to the valley occurred in the 1960’s-70’s when semiconductor manufactures moved to Silicon Valley increasing population growth (Dennis). The population nearly quadrupled from 1950 to 1980 in Santa Clara County, from 290,547 to 1,295,071 (“U.S. Census Bureau: Santa Clara County, California”). As a result, home prices rose, in tandem with the rise of software and internet companies. Apple, Google, Facebook, Adobe, and AOL placed their headquarters in Silicon Valley and subsequently recruited thousands of workers. Before the prominence of software and internet companies, the median home price in Silicon Valley was $245,670 in 1990. This number is about ¼ less than the 2020 single-family median home price of $1.2 million, a time when internet and software companies dominate in the Valley (Compass).

Many tech companies start in or move to Silicon Valley because of agglomeration effects. Agglomeration economies are “the benefits that come when firms and people locate near one another together in cities and industrial clusters” (Glaeser). The gains include reducing transport costs: by gathering close to one another, firms can easily spread goods, people, and ideas. Some argue there are even “intellectual spillover” effects in the atmosphere where firms gather closely. Furthermore, Silicon Valley has direct access to social capital through the hiring process of highly skilled workers who graduate from local high-ranking universities, such as University of California, Berkley and Stanford University. The benefits firms accrue by locating close to one another create positive supply-side complementarities.

As semiconductor manufacturers moved to Silicon Valley in the 1960’s and 1970’s, it became easier for “start-up” technology companies to form as they had easy access to parts for their products due to Silicon Valley’s hub of technology. When companies congregate in similar areas, communication and collaboration become easier as workers in these firms develop professional and personal relationships. Agglomeration also increases the spread of “non-rivalrous” ideas: ideas in which one’s consumption of an idea does not diminish another’s consumption of an idea. The dispersion of ideas ultimately helps to foster innovation (Glaeser). The tech industry’s growth in Silicon Valley exemplifies the concept of agglomeration, which explains the booming population growth and the ensuing housing crisis.

3. Origins of the Affordable Housing Crisis

Silicon Valley land policies make the area unequipped to accommodate large population growth. As the area became and continues to become wealthier, more working-class people are priced out of the market and land policies do not encourage the building of new affordable housing. In San Francisco, rent has increased 6.6% annually (2.5% accounting for inflation) since the 1950’s because of the increased demand for housing coupled with the absence of new vacant lands for development (Fischer). The State of California also ended a 60-year-old program that infused 1 billion dollars each year into redevelopment agencies. These agencies set aside this money for the construction of affordable housing (Gutierrez). Before Silicon Valley experienced its peak economic growth, California passed Proposition 13, “The People’s Initiative to Limit Property Taxation,” in 1978. Under Prop 13, property tax on each residential and commercial building are evaluated by a base year, property taxes cannot increase more than 2% a year, and property taxes are limited to 1% of the assessed values. Homes not sold or constructed since February 1975 are evaluated at their 1975 price, which is used as a base value (“Understanding Prop 13”).

(i) Proposition 13

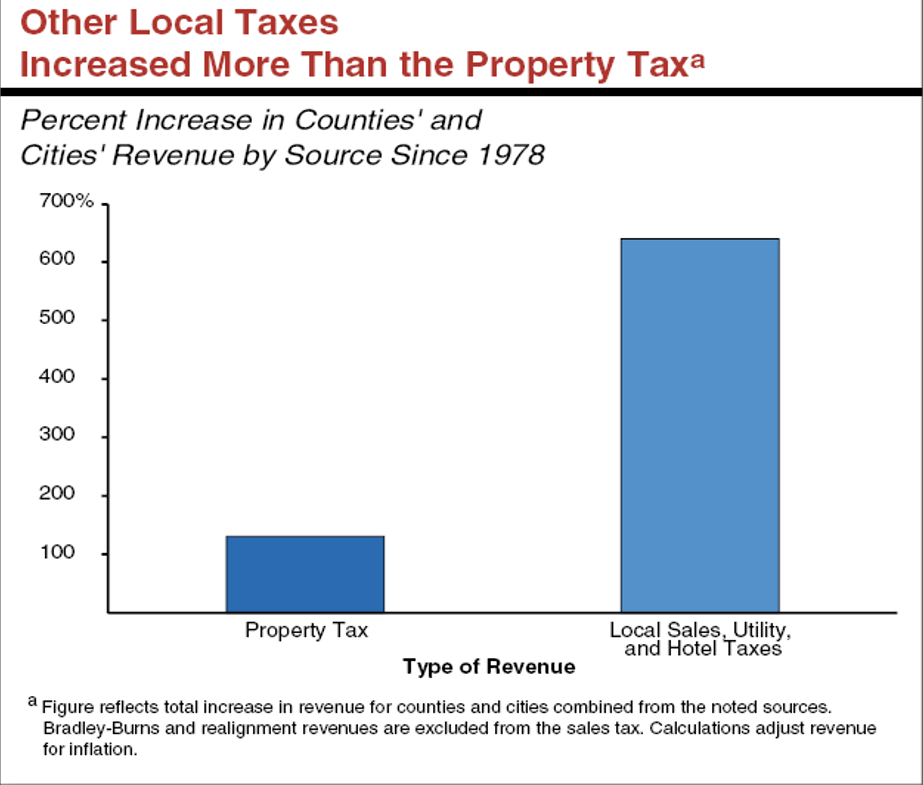

Proposition 13 creates advantages for long-time residents and their families, yet ultimately discourages new residential building by favoring commercial building. At the time Prop 13 was passed, San Jose (a major city in the Silicon Valley) had a real GDP of $37 billion, which increased 643% to its 2019 measured value of $275 billion (Pulkkinen, Weissman). During this time of immense economic and population growth in Silicon Valley, Prop 13 caused cities to favor commercial building: “commercial development to house jobs generates revenue from sources such as payroll taxes, sales taxes, development fees and utility costs, while its occupants require fewer services,” whereas residents require many city services and only generate property tax revenue for the city (Torres). The multitude of tax revenues generated from commercial properties, as well as the large increase in local sales, utility, and hotel taxes in the past 50 years, may create an incentive for cities to approve and expediate commercial permits over residential developments (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percent Increase of CA Property Taxes vs. Local Sales, Utility, and Hotel Taxes since 1978 (source: CA Legislative Analyst’s Office)

Prop 13 also makes it more difficult for new California residents to become homeowners. A survey found that 22% of property owners (those who bought their single-family homes before 1989) pay a mere 6% of property taxes, whereas 39% of property owners (those who purchased single-family homes after 2008) pay 55% of the taxes on those type of homes (Bitter). Many also point out the tax loophole Prop 13 creates for commercial properties, which ultimately may inhibit vital tax revenue to the cities. This funding can be used to revitalize neighborhoods or even for affordable housing purposes for new or low-income residents. In commercial buildings, the California State Legislature only defines a property tax transfer as one in which the transferring partner owns more than 50% of the business. This legislation allows corporations to avoid reassessment of a property by maintaining the building’s original base-year for property tax evaluation purposes. For example, a grocery store built in 1974 could change ownership, yet as long as the original grocery store maintains ownership of 50% of the business, the property is not reevaluated, and the base year of 1975 is used for property tax purposes. Furthermore, there has been some evidence that commercial buildings on average change ownership less frequently than residential properties, which is beneficial for lower property taxes in commercial developments (Sagehorn).

All of these reasons may create an incentive for developers to favor building commercial buildings as they can benefit from the low property taxes designated by Prop 13. Closing this commercial loophole will raise an estimated $11.4 billion in additional tax revenue. This additional revenue can increase funding for public schools and even state-sponsored subsidy programs for housing for low-income populations and/or new CA residents (Thorwaldson).

(ii) Zoning Laws

In the city of San Jose: 94% of land is zoned only for single-family homes (Badger and Bui). The strict single-family zoning creates challenges for developers to create more high-density living options to expand from the current designated lands for apartments that mostly exists around commercial streets and transportation sites. Cities such as Minneapolis and Seattle are considering banning single family zoning altogether. However, San Jose’s mayor Sam Liccardo is considering offering forgivable loans to single-family homeowners who build secondary smaller units on their property and rent them to low-income families (Lopez). It will be difficult to motivate residents to construct new units on their property due to the opportunity costs like the time, energy, and material costs needed to build and rent the smaller unit. Considering that more Silicon Valley workers are living outside the main cities and about 120,000 people endure “super commutes” of 3 hours or longer to drive to their job, it is vital to reconsider zoning laws in major cities to allow increased development of multifamily units that are more affordable than traditional single family homes (Balassari). Reforming zoning laws will also allow for more efficient developments on land already used for housing without the need to acquire new land—preventing any further unnecessary environmental damage.

(iii) NIMBY-ism

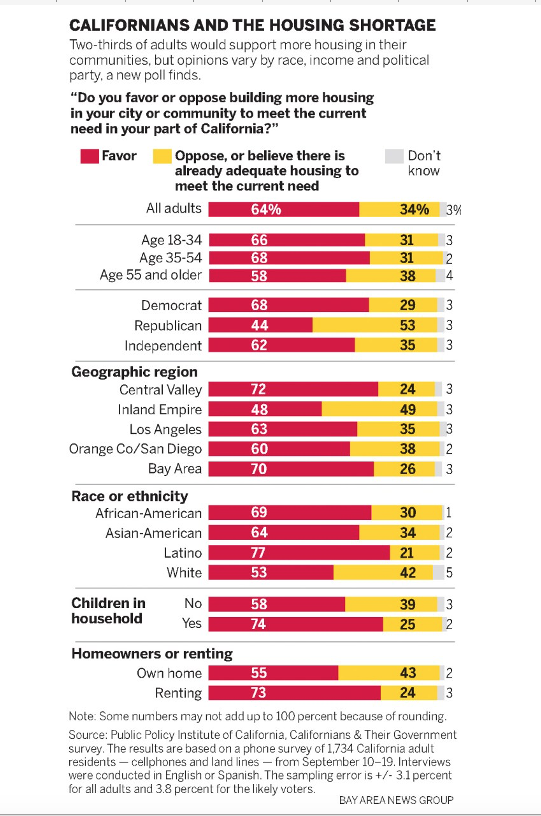

One additional way to increase affordable housing developments is to reform “NIMBY” (Not in My Backyard) attitudes. Much of the main pushback against new affordable housing originates from local residents, often labeled as NIMBYs (Figure 1). Many residents advocate against new affordable housing developments for fear of driving surrounding property values down, pre-conceived stigma against low-income individuals, increased traffic and population density, or general resistance to any sort of change. These attitudes make affordable housing initiatives difficult to pass and intensifies negative conceptions about the concept of affordable housing and the people who may live in these developments.

Often, even if the necessary funds are secured and developers are contacted, affordable housing projects must wait a long time for the city to approve permits. This delay is most often due to resident complaints. Santa Clara met 0.1% of its needed low-income housing, as determined by the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) tool of the California Department of Housing and Community Development. San Jose met 0.1% of its needed low-income housing. By contrast, Santa Clara met 213% of its needed housing for above moderate income and San Jose met 83.1% (“Regional Housing Needs Allocation and Housing Elements”). Education is a key tool to combat NIMBY attitudes. One study done by UCLA Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy Michael Lens disproved the NIMBY common view that low-income residents bring higher crimes. Lens studied Section 8 Vouchers that provides rental assistance to 5 million low-income people nationwide. He found that the connection people observe between voucher households and crime is due to the fact most affordable housing is built in higher-crime neighborhoods, and thus these households are most likely to move to these areas due to limited crime. The voucher households do not tend to bring crime to these neighborhoods (Fung). Understanding studies such as this one is important to increase education that combats the vitality of NIMBY-ism.

Figure 2: Survey of Attitudes towards New Affordable Housing based on Various Factors (source: Bay Area News Group)

4. Role of Tech in the Affordable Housing Crisis

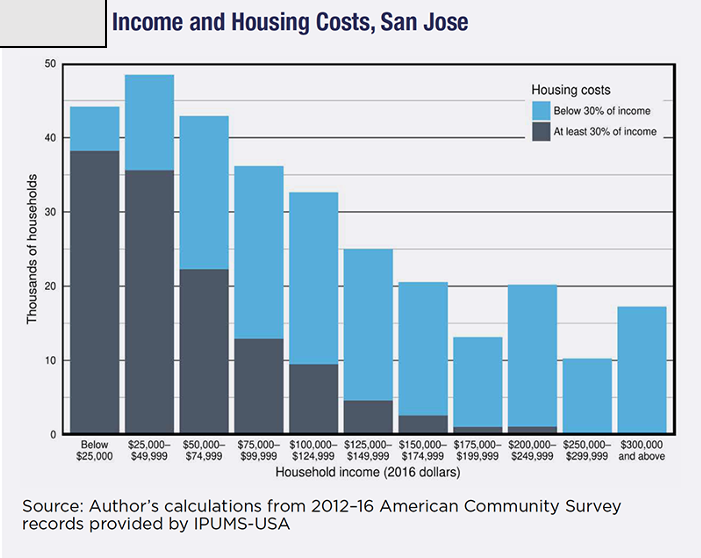

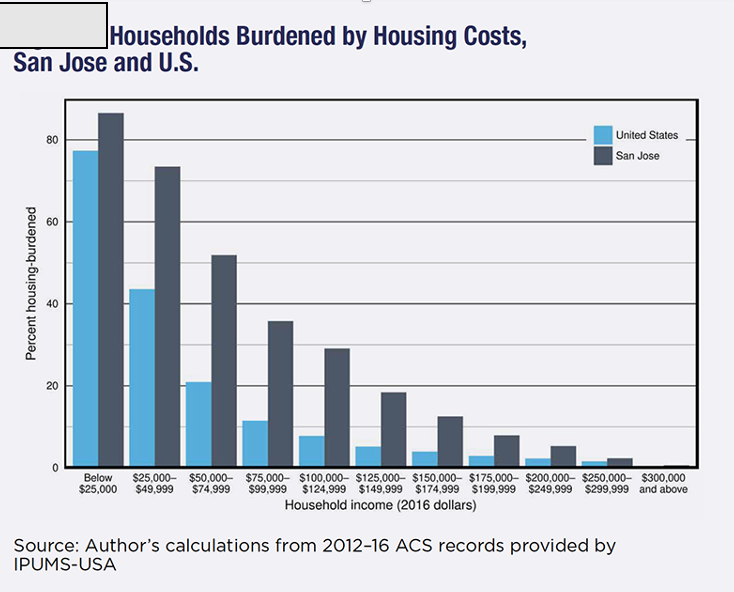

Tech companies play an important role in creating a job market that housing cannot keep up with. Agglomeration effects create extremely rapid population growth in condensed areas, causing previous policies regarding transportation and housing to become inadequate. Statistics prove this chain of events. In May 2019, tech jobs accounted for 20.5% of all employment in the San Francisco Bay Area, which is magnified in cities in the Silicon Valley. In May 2019, 45.6% of all jobs in Santa Clara County were in tech (Avalos). In 2018, close to 36,000 new jobs were created in the Silicon Valley (34% of which were tech jobs, while only 8,400 new residential units were issued permits (“2019 Silicon Valley Index”).The median cost of rent in Silicon Valley: $3,028 versus in the U.S. $1,661 (“Median Rental Rates”). Half of renters, and over a third of mortgage-holding homeowners, spend more than 30% of their income on housing (Malas) (Figure 3). The high cost of living creates enormous wealth gaps, especially when comparing lower-middle class to upper class. In fact, there is a large gap between the national average vs. the San Jose average of the percentage of households burdened by housing costs. The gap between the San Jose percentage of households burdened in comparison to the national average is amplified particularly in the income range of $25,000-$74,999 (Figure 4).

Figures 3 and 4: Housing costs in relation to income in the Silicon Valley show burdens especially across the middle class (source: Manhattan Institute)

Clearly, residential units built in proximity to major tech company headquarters drive residential pricing up. The difference in price between an Apple employee’s home near Apple headquarters and the average home in San Francisco was close to $400,000. One study found that the median home price near Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, CA was around $1.5-$2 million (Ryder) This is triple the price of a home in neighboring counties. When companies make their headquarters in the middle of residential neighborhoods like Apple Park, native low-income residents are displaced due to the unaffordable housing market. These houses are then occupied most often by high-income earners. As tech companies continue to grow, people who cannot afford the housing are forced to move further and further away from headquarter locations or in worse case sceneries, end up homeless.

Wages have also increased for top earning employees, who are usually in the tech industry, while they remain stagnant in other lower-earning sectors. Between 1997 and 2017, hourly wages for the top 10 percent of earners in Silicon Valley increased by 0.7 percent. The most significant decline was for those at the middle-income level. Those in the 50th percentile have seen wages decline by 14.2 percent over the same 20-year period, while those in the 60th percentile have seen a 13.2 percent decline (Sheng). Tech employees make more in the San Francisco Bay Area. The average wage for a software engineer in the San Francisco Bay Area in 2020 was roughly $165,000, while the national average was $104,000. For comparison, the minimum wage in a Silicon Valley city such as San Jose is $15.25, which results in a yearly salary of $31,720—this minimum-wage salary pales in comparison to the six-figure salary made at most tech companies. Considering the median cost of rent in Silicon Valley ($3,028), a person surviving by working one minimum wage job would not be able to afford rent for a year, let alone any other living costs. As tech companies recruit more high-skilled workers into the Valley, housing demand, and thus housing prices will only further increase. Companies must think of these negative externalities before deciding on a Silicon Valley location.

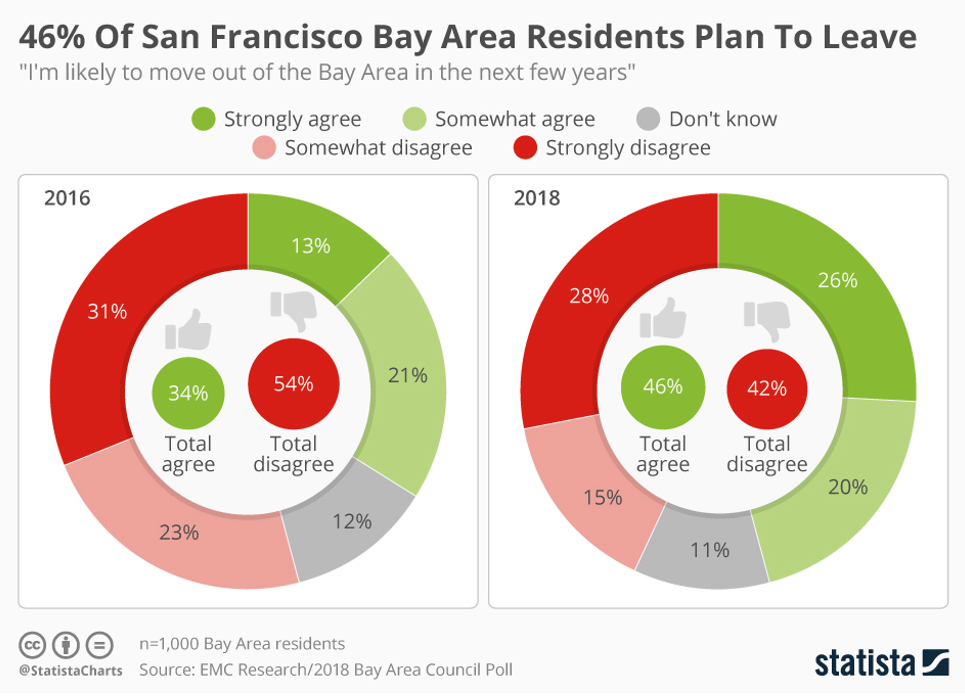

As a result of these statistics, many of those who are unable to afford living in Silicon Valley are beginning to move. California lost a net of 135,600 residents in 2020 (Escalante). As housing prices continue to increase, more residents plan to leave for a more affordable area (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Survey of San Francisco Bay Area Residents’ Attitudes towards Leaving the Bay Area 2016 vs. 2018 (source: Statista/EMC Research)

5. Apple, Google, Facebook address affordable housing (announced late 2019)

Over the years, attention has been called on big tech companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook to acknowledge their roles in the Silicon Valley housing crisis and actively combat it by providing more affordable housing options. In 2013, Apple began constructing its 2,800,000 square feet office building named “Apple Park.” The company now has more than 12,000 staff working in its building, 90% of whom do not reside in Cupertino, the city where Apple Park is located. Apple Park is located in a residential area where only 1.5% of commutes to Apple’s facilities are on public transit (Rogers). The contrast of Apple’s luxe campus in comparison to the surrounding areas is particularly striking from aerial view—noting the vast amount of space the campus takes (Figure 6). One study estimates even the demand for housing in Cupertino alone would go up 284% due to Apple Park’s construction (Rogers). In fact, a 3-bedroom single, family home across the street from Apple Park was sold in 2007 for $795,000. In 2020, that same home now is estimated to be $1.8 million, more than double the price it was 13 years ago (Redfin).

Figure 6: Apple Park and surrounding area in 2016 (source: Matthew Roberts drone footage).

Recently, all three companies have announced their decision to give billions of dollars to mitigate California’s housing crisis. However, we must consider that as for-profit companies, maximizing profits will take precedent for any action they take. These plans are more “investments,” than charitable donations, often allowing the company, in some cases, to act as real estate developers, landlords, and lenders. No specific guidelines have been set in place to regulate these companies in their real estate dealings, which may blur the lines between a tech company’s true role in society. These plans raise the question of the balance between government and the private sector when it comes to issues concerning the public good, such as affordable housing.

Apple announced its plan to “combat the affordable housing crisis” in November 2019. This plan allocates approximately $2.5 billion dollars:

- 1 billion to an affordable housing fund

- 1 billion to a first-time buyer mortgage assistance fund

- 300 million to Apple owned land for affordable housing

- 150 million to a Bay Area housing fund

- 50 million to Destination Home, a non-profit that supports vulnerable populations

Although the plan appears generous at surface-level, a deeper analysis raises clear ethical concerns specifically related to Apple’s allocation of the money as an investment, and not a charitable donation. “The housing programs announced by Apple and other companies are not philanthropy, but commitments to make affordable housing investments — for profit — in the form of corporate land and money. The details vary, but each company said it would allow housing development on land it already owned, and issue loans whose terms and interest rates are implicitly more generous than the terms that developers currently get from banks, but whose true costs will take years to figure out” (Dougherty).

Apple said its plan would, among other things, create an affordable-housing fund that would give the state and others “an open line of credit” to build more affordable housing beyond land that it owns. The company expects to make money from the financing, but for the returns to be lower than what it would earn on investment-grade securities where corporate holdings traditionally lie. Bernie Sanders said of the initiative, “Apple’s announcement that it is entering the real estate lending business is an effort to distract from the fact that it has helped create California’s housing crisis—all while raking in $800 million of taxpayer subsidies, and keeping a quarter trillion dollars of profit offshore, in order to avoid paying billions of dollars in taxes.” If Apple lacks the proper internal regulation in regards to paying required taxes on profits, this points to their penchant to act in the interest of profits over people. This history of behavior gives reason to suspect potential malpractice in developing and renting out housing to vulnerable populations without regulatory oversight.

Apple intends to make available land it owns in San Jose worth approximately $300 million to the development of new affordable housing. The funding commitment to California is expected to take approximately two years to be fully utilized depending on the availability of projects. Capital returned to Apple will be reinvested in future projects over the next five years.Apple has no clear indication of how it plans to use the “capital” it will gain from building new affordable housing. Instead of donating the land and developing a sort of public-private partnership with the city in which the city accrues the benefits of rent, Apple will oversee each unit from start to finish. There must be an underlying profit-driven or privately motivated incentive for Apple to keep ownership of the land and rent units, otherwise Apple would have simply donated the land for affordable housing. A potential self-interested reason for Apple to own affordable housing on its own land is to create advantages for Apple’s workers to be housed first. If this is the case, a third-party should be called to regulate the housing distribution process through an entry system which places those who absolutely need affordable housing at the top of the list before Apple can obtain permits to start building.

In addition to these initiatives, Apple is working to identify private developers who, with the right financing and investment, are ready to start construction on affordable housing projects in the Bay Area immediately. There are clear ethical concerns over private company and private developer interactions for public good projects. Apple has yet to clarify whether there is a third intermediary regulating these interactions. In the long-term, it is unclear who will ultimately be benefitting from these affordable housing projects.

Facebook announced its plan to invest $1 billion into affordable housing in mid-October 2019. Unlike Apple, Facebook chose to allocate $250 million of its funds into a public private partnership with the state of California for mixed-income housing on excess state-owned land in communities where housing is scarce. A public-private partnership in housing allows the private organization (Facebook) to utilize “economies of scope,” which might increase the efficiency at which the housing is built and maintained. Economies of scope are linkages between multiple divisions that one entity controls, which ultimately reduces costs (such as the private contractor controlling construction, design, and services). (Iossa and Martimort 2012). Although a public-private partnership may make sense regarding the immediate need for more housing, clear regulations must be put in place when it comes to the revenue from the housing and who gets the priority to be housed first.

Facebook also pledged $225 million of land in Menlo Park. This is land Facebook previously purchased, that is now zoned for housing, similar to Apple’s pledge of $300 million in land. Facebook states it plans to produce more than 1,500 units of mixed-income housing on this land. Note the language of “mixed-income.” The purpose of Facebook’s plan was to “help address the affordable housing crisis in California.” It is misleading the public to claim that Facebook will use this land to fund “mixed-income” housing instead of the much-needed affordable housing. Like Apple, a clear concern is whether the company will prioritize housing its own employees before it gives the opportunity to others. Here, government needs to push Facebook to provide clear and concise language as to how it plans to house individuals with an emphasis to prioritize people based on need. It is only then the affordable housing crisis, which Facebook says it pledges to help, can be honestly addressed.

Lastly, Google—another Silicon Valley tech giant announced an additional $1 billion investment in housing across the Bay Area. Most of the money, as with Apple and Facebook, is given in the form of company land. Over the next 10 years, Google proposes to repurpose at least $750 million of Google’s land, most of which is currently zoned for office or commercial space, as residential housing. The Google-owned land will “support the development of at least 15,000 new homes at all income levels in the Bay Area, including housing options for middle and low-income families.The housing development plan is similar to Apple as “mixed-income” housing built on company-owned land.

6. The Dichotomy of Mixed-Income Housing

If California needs to build 3.5 million new affordable housing units by 2025, Google, Facebook, and Apple should place priority on building low-income housing on this land, instead of building mixed-income housing (Woetzel et al). Mixed-income housing is housing in which units are built for various income levels. The perceived benefits from mixed-income housing stems from poverty alleviation, improving property values, promoting diversity in interactions among residents, and improving conditions for low-income residents (Levy et al). However, when private companies—aiming to profit maximize in investments—state that they plan to build mixed-income housing this may imply the companies will prioritize building market-rate housing units they could potentially benefit from, with only a few subsidized units for low-income residents. These subsidized units would easily be in high demand, causing extremely long waiting lists and less people permanently housed. In fact, an analysis of U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Hope IV (Hope IV is a HUD sponsored program that provides rental assistance to low-income people) development proposals found that a majority of mixed-income redevelopments suggest that those with the lowest-income should constitute the least number of units occupied in the new housing (Vale and Shamsuddin). Thus, the “mixed-income housing” would in actuality be more for middle to even high-income residents.

Evidence suggests, even when allocated fairly among income levels, mixed-income housing may not have positive benefits on low-income residents. One study found that in a Chicago Housing Authority mixed-income redevelopment project, where 7,700 out of 17,000 units were designated for public housing, some social tensions arose across income groups. Specifically, researchers did not find evidence that mixed-income housing increases low-income individuals’ “social capital,” or they did not seem to directly benefit from the perceived net-working or role modeling affects of living with higher income individuals (Chaskin and Joseph). For highly vulnerable populations, a model of inclusion must be incorporated into mixed-income developments, where residents actively seek to bridge differences that result from income through understanding.

If tech companies desire to truly help the affordable housing crisis, their first concern should be building more affordable housing. Mixed-income developments may be successful if low-income units make up the majority. This also includes giving special consideration for units to homeless individuals before others, in addition to providing a combination of supportive services, such as case-management for all residents.

For private companies, proper affordable housing developments would mean a long-term commitment to helping those society deems as outcasts, which may not be ultimately an attractive investment for profit-maximization. However, a good reason for adding more affordable housing options is the benefit companies may experience from increasing the amount of spendable income Silicon Valley residents may have: “California’s housing shortage costs the state more than $140 billion per year in lost economic output, including lost construction investment as well as foregone consumption of goods and services because Californians spend so much of their income on housing” (Woetzel et al). If tech companies concentrate on ensuring affordable housing is their top priority by primarily building low-income designated units, even in mixed-developments, residents can improve their quality of life by allocating their money to other expenses other than housing.

7. The Future of the Silicon Valley

Per the statistics provided in Section II, Silicon Valley’s housing crisis is not one of accessibility to housing, but affordable housing. Private companies creating mixed-income housing on their privately-owned land does not fully address the issue of increasing the amount of affordable housing. We must also consider how we will keep profit-maximizing companies transparent and accountable while they act as landlords.

The idea of tech companies possibly expanding their business to real estate is perhaps a vision of a dystopian future. If the government cannot regulate these companies in their for-profit transactions effectively, potential issues of monopoly practices will likely arise, especially in high-density areas. Housing opens the door to private companies controlling other non-traditional sectors in the future. If companies can build housing on their own land and act as private landlords, what could potentially stop them from creating their own privately-owned mini societies? In the future, we could see Apple or Google owned hospitals, schools, and pharmacies.

The money given by these tech monopolies does not advocate for urban planning policy issues that have more of a long-term impact. The money donated does not work to change zoning laws nor does it work to systematically change building codes to encourage long-term change. The pledged funds also do not address the lack of accessible public transportation currently in Silicon Valley. In order to alleviate the Silicon Valley housing crisis, true philanthropy towards non-profits addressing homelessness/housing issues must be combined with enacting legislation (amending zoning laws to allow for more multi-family buildings) and increasing education (reforming NIMBY-ism). Above all, tech companies must commit to making conscious decisions in the Silicon Valley to incorporate ethics into their business practices by taking moral responsibility to improve the social good in the area where they build their wealth.

It is clear that the government must also play a distinct role in regulation to control possible corruption or monopolies from developing in the Silicon Valley. If companies truly want to build more affordable housing on their own land, they must forge partnerships with the public sector to gage public need and set a clear precedent. Recently, Facebook and Google announced their plans to have most of their workers work from home until July 2021, with Twitter giving their workers an option to work from home permanently. If the work from home culture is promoted, we may see a significant number of workers leave Silicon Valley, which would ultimately drive housing prices down (Sandler). This is a promising avenue for the future of the Silicon Valley yet may be hard to realize as many workers may not want to leave the Valley to work elsewhere due to salary reductions, among other reasons.

Ultimately, we must create a culture of accountability. If these companies make billion-dollar commitments to the affordable housing crisis (the crisis that they in part helped to create), we should expect them to fulfill this goal and not use their funds to create incentives for profits.

Works Cited

Avalos, George. “Tech Jobs Soar to All-Time Record in Bay Area.” The Mercury News, The Mercury News, 5 July 2019, www.mercurynews.com/2019/07/05/tech-jobs-soar-all-time-record-heights-bay-area-apple-adobe-facebook-google/.

Badger, Emily, and Quoctrung Bui. “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: A House With a Yard on Every Lot.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 18 June 2019, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html.

Baldassari, Erin. “Bay Area Super-Commuting Growing: Here’s Where It’s the Worst.” The Mercury News, The Mercury News, 9 Dec. 2019, www.mercurynews.com/2019/09/11/supercommuting-is-not-just-for-central-valley-dwellers-map-shows-growth-in-bay-area-commutes/.

Bizjournals.com, www.bizjournals.com/sanjose/news/2019/10/24/why-is-the-peninsula-so-afraid-of-housing.html.

Bitters, Janice. “How Has Prop. 13 Affected Tax Distribution in Santa Clara County?” San José Spotlight, 16 June 2020, sanjosespotlight.com/how-has-prop-13-affected-tax-distribution-in-santa-clara-county/).

California Department of Housing Planning and Community Development. Regional Housing Needs Allocation and Housing Elements, California Business, Consumer Services and Housing Agency, 29 June 2019. www.hcd.ca.gov/community-development/housing-element/index.shtml.

Chaskin, R.J. and M. Joseph (2011), Social interaction in mixed-income developments: relational expectations and emerging reality. Journal of Urban Affairs, 33 (2), pp. 209-237.

Compass. “What Did Bay Area Home Prices Look Like 25 Years Ago?: California Real Estate Blog.” Compass, 9 June 2016, compasscaliforniablog.com/what-bay-area-home-prices-looked-like-25-years-ago/.

Compass. “Santa Clara County Real Estate,” Mar. 2021, www.bayareamarketreports.com/trend/santa-clara-home-prices-market-trends-news.

Dennis, Michael Aaron. “Silicon Valley.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 12 Sept. 2019, www.britannica.com/place/Silicon-Valley-region-California.

Dougherty, Conor. “Why $4.5 Billion From Big Tech Won’t End California Housing Crisis.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/business/economy/california-housing-apple.html.

Ellison G, Glaeser E, Kerr W. 2010. What causes industry agglomeration? Evidence from coagglomeration patterns. Am. Econ. Rev. 100(3):1195–213

Escalante, Eric. “California’s Growth Rate at Record Low as More People Leave.” abc10.Com,

ABC, 16 Dec. 2020, www.abc10.com/article/news/local/california/californias-growth-rate-at-record-low-as-more-people-leave/103-3f814e19-ffe1-44af-90c0-a49168be4a60.

Fischer, Eric. Employment, Construction, and the Cost of San Francisco Apartments, 1 Jan.2014, experimental-geography.blogspot.com/2016/05/employment-construction-and-cost-of-san.html.

Fung, Lisa. “Do the Poor Bring Crime with Them?” UCLA Blueprint, UCLA, Sept. 2018, blueprint.ucla.edu/feature/do-the-poor-bring-crime-with-them/.

Garosi, Justin and Brian Uhler. “California Losing Residents Via Domestic Migration.” California Losing Residents Via Domestic Migration [EconTax Blog], Legislative Analyst’s Office, 21 Feb. 2018, lao.ca.gov/LAOEconTax/Article/Detail/265.

Gutierrez, Melody. “California Housing Crisis Spurring Lawmakers into Action.” San Francisco Chronicle. 2017.

Levy, D. K., McDade, Z., & Bertumen, K. (2013). Mixed-income living: Anticipated and realized benefits for low-income households. Cityscape, 15, 15–28

Lopez, Nadia. “Is Banning Single-Family Zoning Possible in San Jose?” San José Spotlight, 9 Apr. 2020, sanjosespotlight.com/is-banning-single-family-zoning-possible-in-san-jose/.

Malas, Nour. “California Has the Jobs but Not Enough Homes.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 19 Mar. 2019, www.wsj.com/articles/california-has-the-jobs-but-not-enough-homes-11553007600?mod=searchresults&page=1&pos=1#comments_sector.

“Median Rental Rates.” Silicon Valley Indicators, Joint Venture Silicon Valley, Nov. 2019, siliconvalleyindicators.org/data/place/housing/housing-affordability/median-rental-rates/.

O’mara, Margaret. “Don’t Blame Tech Bros for the Housing Crisis.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 Nov. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/30/opinion/sunday/housing-crisis-silicon-valley.html#commentsContainer.

Pulkkinen, Levi. “If Silicon Valley Were a Country, It Would Be among the Richest on Earth.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 30 Apr. 2019, www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/apr/30/silicon-valley-wealth-second-richest-country-world-earth.

“Regional Housing Needs Allocation and Housing Elements.” HCD Regional Housing Needs Allocation and Housing Elements, California Department of Housing and Community Development, 30 July 2020, www.hcd.ca.gov/community-development/housing-element/index.shtml.

Rogers, Adam. “If You Care About Cities, Apple’s New Headquarters Sucks.” Wired, Conde Nast, 2019, www.wired.com/story/apple-campus/.

Ryder, Savannah. The Effects of Silicon Valley Companies on the Bay Area Housing Crisis. Diss. Columbia University, 2018.

Sagehorn, Derek. “Proposition 13 Is Broken. Annually Reassessing Commercial Properties Will Fix It.” SCOCAblog, 4 Sept. 2019, scocablog.com/proposition-13-is-broken-annually-reassessing-commercial-properties-will-fix-it/.

Sandler, Rachel. “Facebook Is The Latest Company To Extend Remote Work Until July 2021-Here’s When Other Companies Plan To Go Back.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 7 Aug. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/rachelsandler/2020/08/06/facebook-is-the-latest-company-to-extend-remote-work-until-june-2021-heres-when-other-companies-plan-to-go-back/.

Sheng, Ellen. “The Shocking Truth: In Silicon Valley Wages Are down for Everyone but the Top 10% .” CNBC, CNBC, 4 Dec. 2018, www.cnbc.com/2018/12/03/in-silicon-valley-wages-are-down-for-everyone-but-the-top-10-percent.html.

Thorwaldson, Jay. “Off Deadline: An $11.4 Billion Question: Can Proposition 13 ‘Loophole’ Be ‘Corrected’?” News | Palo Alto Online |, 6 Apr. 2018, www.paloaltoonline.com/news/2018/04/06/off-deadline-an-114-billion-question-can-proposition-13-loophole-be-corrected.

“Understanding Proposition 13.” Office of the Assessor, Santa Clara County, www.sccassessor.org/index.php/faq/understanding-proposition-13.

“U.S. Census Bureau: Santa Clara County, California.” Census Bureau QuickFacts, U.S. Census Bureau, www.census.gov/quickfacts/santaclaracountycalifornia.

Vale, L., and S. Shamsuddin. “In the US, Mixed Housing Developments Aren’t Working for Low-Income Families.” CityMetric, NewStatesman, 13 Feb. 2015, www.citymetric.com/horizons/us-mixed-housing-developments-arent-working-low-income-families-698.

Weissmann, Jordan. “America’s Most Important Cities: 1978 vs. 2010.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 26 June 2012, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/06/americas-most-important-cities-1978-vs-2010/259002/).

Woetzel, Jonathan, et al. “Closing California’s Housing Gap.” McKinsey & Company, McKinsey & Company, 27 Apr. 2018, www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/urbanization/closing-californias-housing-gap.