Fintech Payday Lending: The Case of Wonga

By: Yashi Wang

Early accounts of UK online payday lender Wonga sounded like the first chapters of a revolutionary fintech success story. Twelve years later, Wonga has collapsed into administration, overseen by Grant Thornton UK LLP. As of its collapse in August 2018, Wonga owed unsecured creditors a total of £83.3 million (US$104 million), including £45 million (US$56 million) in payouts. This insolvency is the culmination of thousands of registered complaints, intermittent scandals, FCA financials controls, and more.

The ethics behind payday lending, as well as Wonga’s behavior in particular, is worth examination. In this case, elements of usurious profiteering, information asymmetries, aggression and exploitation, and negative externalities offend both distributive and commutative justice. These violations are also largely inconsistent with Wonga’s supposedly crucial and benevolent role in consumer credit economy, as used in its defense narrative.

Introduction to Payday Lending

Payday loans refer to short-term, high-cost, unsecured loans of a relatively small sum. There are a number of typical features. Due to interest accumulation, the loans are designed to be paid back as soon as possible — often on the borrower’s next payday. (Wonga emphasizes its loan durations are determined by the consumer, and can end as soon as repayment is made.) The repayment is made by either a post-dated check, or authorized direct withdrawal from the borrower’s accounts.

Payday lenders are generally frank about upfront costs of loans, but hidden penalty charges, roll-over fees, and loans taken out to repay other loans can generate additional hundreds or thousands of pounds in debt, surpassing the original loan (Goff). At the same time, these loans are known as easier to access, attractive to borrowers turned away elsewhere.

Wonga describes itself as a ‘leading digital financial service business’ (Wonga Group 7). It has optimistically said that its borrowers do not resemble vulnerable and struggling poor folk, but ‘tech-savvy young professionals’ who previously used traditional credit services (Murray-West). Its site suggests loans are appropriate for occasional financial emergencies and unexpected obligations.

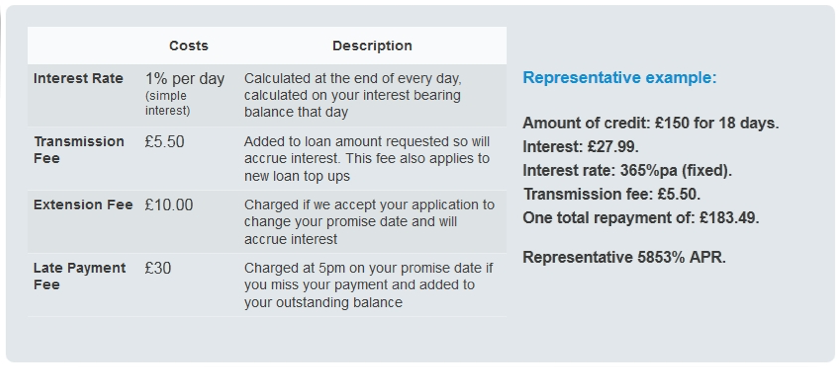

Fig. 1 is a capture of the loan-affiliated costs from Wonga.com, prior to caps in compliance with 2015 Financial Conduct Authority regulations. According to the site, first-time customers were limited to £400 for a one-installment ‘short term loan’, £500 for a 3 month flexible loan, and £600 for a 6 month flexible loan.

Source: Wonga.com

Wonga: “Rags to Riches to Rags”

Before Wonga itself existed, its essence appeared as the project ‘SameDayCash’ in 2007. For a year, the site delivered the internet’s first fully automated loans to clients across the UK. During this year, SameDayCash faced default rates of roughly 50%, which only confirmed to its creators that existent standards for loan approvals were insufficient. SameDayCash was, from its inception, an experiment used to gather data about borrower behavior and better predict risk of default (Shaw). In July 2008, Errol Damelin and Jonty Hurwitz fully launched Wonga, ready to redefine the short-term loan industry.

While the industry was relatively inactive when Wonga was founded, it began to see rapid growth in a loosely regulated market. Between 2006 and 2009, credit extended in the UK through payday loans quadrupled from an estimated £0.33 billion to £1.2 billion (Beddows and McAteer 7). An analysis of business properties across English indices of deprivation — a governmental measure of local poverty — also reflects a growth in the number of payday lending and pawnbroking businesses since 2008. This growth was most noticeable in ‘deprived’ areas (Stabe and Bernard). Of course, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) helped amplify the industry as UK banks restricted their lending and reluctantly catered to only the most financially sound borrowers possible. Credit card interests were high. Poorer borrowers were both financially stressed and increasingly limited in cash sources (Shaw). Wonga’s automated platform offered 24/7 service, instant approval, and immediate fulfillment in a convenient and user-friendly venue. In exchange, customers paid the highest interest rates even among payday lenders at 4214% APR.

Payday credit in the UK reached approximately£3.7 billion by 2012, tripling since the GFC (Beddows and McAteer 7). At the height of its success around 2012, Wonga was delivering £1.2 billion of these loans and posted a net profit of £62.5 million. However, this would be peak performance for UK’s largest payday lender. In May 2012, the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) demanded Wonga correct its debt collection strategies (Osborne, “OFT Criticises”). Wonga’s first known instances of aggressive and possibly fraudulent collection tactics were traced back to as early as 2008. Evidence surfaced in 2010 showing Wonga had sent letters to borrowers struggling with payment. The letters implied the borrowers were committing fraud and that legal action may be taken against them, though no such evidence existed for most.

Through 2013 and 2014, a series of advertisement spots by Wonga also went under investigation. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) subsequently banned some for irresponsible representation of ease and lack of consequences in payday lending. Others were flagged for marketing towards students and children.

Short-term credit regulation and reform became audible in political conversation after the 2010 UK general elections. Stella Creasy, a Labour Party MP, notably lead the discussion. She criticized the payday loan industry’s exploitation of a destabilized post-crisis economy and vulnerable demographics (Jones and Collinson). “Legal loan sharks are circling our poorest families,” she wrote in a 2011 Guardian column. “They’re watching them struggle and they’re sensing a business opportunity.” A partnership with MPs across parties secured a vote on the introduction of caps on credit costs, despite elusive commitment (Creasy).

In 2013, Wonga raised its APR to 5853%, which triggered increased calls for cost caps on credit (Osborne, “Wonga Increases”). On April 1, 2014, UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) assumed regulation of consumer credit. In 2014, Wonga also agreed to pay compensation of over £2.6 million to around 45,000 customers for aforementioned unfair and misleading debt collection practices (Patrick). Remediation costs and anticipation of FCA financial controls led profits to fall 53% in 2013.

In October 2014, due to its inadequate affordability assessments, Wonga writes off £220 million of loans to 375,000 borrowers affected by such practices in compliance with FCA. Then in December, Wonga took further steps by cutting its interest rates, missed payment fees, and transmission fees. On January 2, 2015, FCA’s price cap on High Cost Short-Term Credit (HCSTC) took effect. This was comprised of the initial cost cap, which caps interest at 0.8% per day, a £15 cap on fixed default fees for borrowers who struggle to repay, and a total cost cap such that the amount a borrower pays for her loan in interest and charges must not be more than the amount of money borrowed in the first place (Financial Conduct Authority). These caps ensured a limit to spiraling debt while still leaving a ‘viable market’ intact. The FCA estimated 70,000 people would lose access to loans in the following months, but were likely better off for it. Between 2014 and 2015, Wonga’s loans halved. Its pre-tax losses increased from £37 to £80 million and have remained negative since. Amidst its financial struggles, a data breach in 2017 further impacted its reputation as a company that broke into the tech scene through harnessing big data.

Overwhelming customer compensation claims to the Financial Ombudsman Service, which are each associated with a sizeable case management fee, put Wonga at risk of insolvency. In a last effort, Wonga collected £10 million from shareholders on August 4, 2018 (Johnson). However, Wonga ultimately determined it could not return to profitability. On August 31, 2018, Wonga stopped accepting customers and went into administration under Grant Thornton International. Under administration, Wonga has been selling its assets, collecting loans, and continuing to identify creditors. Its claimants rank as unsecured creditors, and the number of compensation claims has swelled to 49,000 as of the March 2019 administrators’ report (Laverty). Intended refunds are to be made by January 2020, but the sheer volume of redress claims and the company’s insufficient assets mean that the refunds will be short of claimants’ entitlement. There exists interest in Wonga’s technology and its loan book, whose buyer would be entitled to collecting existing debts but would not be liable for the compensation payouts (Jolly). The Archbishop of Canterbury was reportedly leading a discussion to purchase Wonga’s £400 million loan-book with the Church of England’s assets, to protect borrowers from a more aggressive buyer, but has since withdrawn its consideration (Burgess). There has not been a confirmed acquisition, and Grant Thornton is seeking to extend administration by 12 months into August 2020 in order to continue realizing assets and eventually distribute payouts.

ETHICAL ANALYSIS

The rapid growth of the industry and any initial satisfaction from customers are not to be mistaken as evidence of ethical practice. Wonga’s behavior is arguably usurious and fraudulent in ways that clearly defy commutative and distributive justice.

Usury in Payday Lending

Moral criticism of the payday loan industry is not contemporary. A number of ancient and medieval societies in the West condemned ‘usury’, initially defined as charging of interest on loans. Forexample, usury conflicted with the duty of charity to the poor; interest would also widen the inequalities between a necessarily richer creditor and a poorer debtor (Visser and Macintosh 182-184).

Medieval Scholastics had a rich body of usury doctrine: they found poena conventionalis, an extrinsic title to interest from the Roman tradition, to be acceptable. This title essentially allows the contractual demand of payment in excess of the loan in the case of default (Poitras 13). Over time, lucrum cessans, or the opportunity cost of alternative investments, became an acceptable justification of interest (Poitras 14). Through the development of economic theories since, usury now conventionally describes the excessive charging of interest, which is a far more subjective definition.

“We do small, short-term things, and the cost of delivering that service is high. Catching a cab might be expensive, but it’s convenient and nobody complains that being charged £15 for getting across London is immoral.”

“The pricing is a function of value. We’re not trying to build the cheapest product in the world; we’re trying to build the best product in the world and the best product services a need and it costs money.”

— Errol Damelin, Co-founder (Shaw)

In addition to the above statements, the risk taken by the lender is typically used as justification for the astonishing representative APR charged. However, Wonga only carries the illusion of a ‘premium product’. Its risk is not what it is represented as, the price gap with competitors is likely not a function of product superiority, and its costs are not as high as it might present.

Wonga claims low default rates comparable to credit cards: the technicalities of this will be later explored, but assuming its truth, the magnitude of risk that Wonga takes as a lender is clearly no longer compatible with the cost of its service. The best product argument for its APR, well over its UK competitors, is not sound. Even between payday lenders, evidence of classical price competition is unclear. Under a price ceiling, data points from Colorado show that on average, loan prices moved collectively towards the legislated price ceiling over time. DeYoung and Phillips interpreted this as consistent with the presence of implicit collusion between payday firms (27). Of course, the sky was the limit in the UK prior to 2015.

Wonga’s ability to satisfy its purported demographic and solve their occasional unexpected personal issues is doubtful. If payday loans truly had positive effects of helping customers smooth personal financial shocks and properly manage other payments, as with the purported ‘standard customer’, loan access presumably correlates with high credit scores. A study of consumer financial health across U.S. states, which vary in loan availability, revealed no such relationship (Bhutta).

Instead, it’s frequently observed that the payday loan industry exploits the vulnerability of payday borrowers who are by definition desperate and risky, who lack alternative resources. What preserves Wonga’s profitability? What are the costs of delivering the payday service?

Industry pricing is primarily a function of loss rates and customer acquisition cost (CAC) (Beddows and McAteer 15). Supposedly, the default rate has been driven quite low, so CAC is likely the dominant force in Wonga’s costs, and a cost that is certainly difficult to minimize for an entity without brick-and-mortar presence in a maligned industry. For profitability, this CAC per customer must be lower than the fees earned from the marginal borrower, notthe marginal loan. Lenders break even when total pre-tax revenue from a customer equates her ‘Customer Lifetime Value’ (Beddows and McAteer 16). To break even, and clearly to make significant profit, the company needs to maximize the customer lifetime value, thus revealing a dependency on repeat borrowing. Ernst & Young’s study of the Canadian market indicates the operating costs incurred from serving new customers represented 85% of the total costs (34).

Note that Wonga appears to utilize strategic (relationship) pricing. Return borrowers are offered increasingly larger loan limits. Due to the nature of the service, costs to the lender don’t change much between loans of varying sizes. Not only does the lender depend on repeated loans for profitability, but the revenue structure is designed to increasingly benefit over the course of the relationship.

Stegman and Faris’ analysis based in North Carolina also concludes that repeat business is crucial to payday lenders’ performance. The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants’ analysis, using a business model analysis of UK lenders’ financials, came to the same conclusion (Beddows and McAteer). US-based Consumer Financial Protection Bureau arrived at a number of useful statistics: over 80% of payday loans were rolled over or succeeded by more loans within 14 days. Over 80% of loan sequences do not amortize: loan sizes ultimately end the same or larger. Most borrowing occurs in this form of a continuous sequence of loans, rather than successive but distinct periods of borrowing, which might allow the narrative of payday loans as solutions to distinct financial problems. Instead, these figures show a numerical approximation of the spiral of debt that many borrowers like Wonga’s customers fell into.

APRs of as high as 5,853% are justified by short loan terms, but quick and successful repayment is not the best case scenario for Wonga. When the first repayment is unsuccessful and customers take steps to extend, rollover, or take out more loans to repay the first, the interest begins to approach the representative APR.

Responsibility and Transparency

Bar-Gill and Warren made an extensive case in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review that, analogous to physical products like infant car seats and drugs that are inspected and regulated for safety, financial products need to be inspected and regulated as well (2).

“A philosophical conception of fraud, inspired by Kant, defines it as denying to the weaker party in a financial transaction (such as a consumer or investor) information that is necessary to make a rational (or autonomous) decision.”(De Bruin)

On the surface, Wonga’s Code of Practice contains statements such as,

“Our mission is to solve consumers’ occasional, urgent and short-term cash flow problems with an equally short-term solution. We base our commitment to responsible lending on transparency, flexibility and extreme selectivity – believing it’s possible to provide credit in a way that suits consumers, not lenders.” (Wonga Group 6)

Yet the profitability of such companies come from sky high interest rates and repeated borrowing mechanisms like rollovers. In Wonga’s business model, rational profit maximization conflicts with truly responsible lending and borrowing decisions. In such a circumstance, the free business-consumer relationship that the government was so hesitant to regulate is not cooperative and not self-regulated. The relation is parasitic, rather than symbiotic, even fraudulent.

Many of Wonga’s advertisements and sponsorships were heavily criticized, and the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) banned a number of them for irresponsible representation of its services. One advertisement was flagged for including the language “you can even pay back early and save money” while leaving out its representative APR, which implied falsely that Wonga’s loans were cheaper than other lenders’ (Osborne, “Wonga Banned”). Another advertisement implied that their 5,853% RAPR was ‘irrelevant’, by trying to explain that this figure held different meaning for a short-term loan than conventional long-term credit (Press Association). Yet another was banned for implying “taking high-interest loans could be done lightly”; it was also investigated for playing in daytime, when children, unemployed, and other vulnerable viewers are most susceptible (Meyer). More went under fire for irresponsible marketing towards nonessential purchases, student tuitions, and so on.

Wonga has insisted it offers transparent and clear delivery of information prior to the application process using its slider system, which illustrated the amount of credit, interest cost, transmission fee, and total repayment amount (Wonga Group 23). Indeed, what little regulation existed before 2015 did at least require elements of transparency. For example, the APR rates (rather than simply short-term rates that could be creatively presented) were required to be prominently displayed.

However, the costs associated with extensions are not visibly presented facts. Wonga claims “it does not wish to promote the availability of extension” (24). While the information is available, the previous statement is an admittance that they do not want to make it accessible until ‘the event that a customer applies for extension’, i.e. until the customer is in real need of the extension. By this point, it is doubtful that the borrowing decision is fully autonomous, much less rational.

An Imperfect Customer

One of Wonga’s partners at a venture capitalist firm commented, “Errol [Damelin]’s view of the world was ‘consumers are smart, I’ll charge whatever they’re willing to bear because I believe in the market’” (Williams-Grut). Evidence denies that a ‘smart’ customer, empowered with rationality and autonomy, is a realistic assumption.

A study evaluated contemporary money culture and found that borrowers often don’t enter into these loans from the perspective of lacking money, but translate “their pressing needs and wants in terms of money” (Langley et al. 42). These needs and wants encompass both genuine financial difficulties and frivolous purchases, but their important discussions show that borrowers understand payday loans as access to money rather than a credit-finance concept (43).

Even defenders of payday lending like Mann and Hawkins have acknowledged that a normal customer under normal circumstances, of ‘normal intelligence’, does not “easily evaluate the risks and rewards of a payday lending transaction”, especially of the cost of an unsuccessful repayment transaction or ultimate failure to repay (881-882). They also suspect heuristic and optimism biases — flaws of judgement typical especially in quick exercises — in a customer’s consideration of a loan offer.

Moreover, the role of speed of approval, in which Wonga takes great pride, shortens the time frame for reconsideration and price comparison in the borrowing decision, conceivably contributing to a less informed borrowing decision.

Irresponsible Affordability Assessments

In light of customers’ flawed understanding, Wonga’s history of insufficient affordability assessments is especially troubling.

The Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), a government-authorized agency for settling similar disputes, released a report on payday lending in 2014. Ombudsmen commented that even when unaffordability does not play a significant part in a registered complaint, it was largely due to perspective and framing (66). One pointed that they understood the customers’ sense of irrationality in complaining that the loan they received could not be afforded and should not have been offered, when they themselves had made the request for the money under stressed circumstances. In fact, Ombudsmen believed that affordability was the root cause of many complaints that did not explicitly cite it, and more complaints would rush in once a company’s duty to assessment was better publicized alongside the 2015 FCA regulations. Subsequent figures show that the number of complaints did surge.

The FOS has made publicly available 725 decisions regarding Wonga from April 1, 2013 to August 31, 2018 (Financial Ombudsman Service). In the case of a Mr. W, Wonga neglected to consider subsistence costs and other credit commitments. The adjudicator for a Miss S noted that for all its claims of thorough assessment, Wonga does not provide the FOS with evidence or results generated from checks. Ms. M had an unstable income and defaulted on a credit card, but Wonga continued to offer loans, despite having performed a credit reference agency check. Multiple ombudsmen noted that, in fact, a series of payday loans should itself indicate a reliance on loans and an affordability check.

The following case of Lorraine is drawn from a survey conducted by The Guardian that collected readers’ experiences with Wonga.

Lorraine borrowed £280 from Wonga eight months ago to buy food for her and her autistic son and found herself taking out a new loan to clear the debt after 15 days. Lorraine, who is on benefits, has taken out a new loan every month since then and now owes £435.

“I had always managed to pay it back but when it came to the last time I was really worried about how I was going to do it so I told them I was having problems and I have agreed to repay it over three months,” she said. Lorraine said her income was not enough to enter into a repayment plan with Wonga but she lied on the online form to get it agreed: “I had to calculate it, to make sure I put in enough [income] to be accepted. I was really desperate.”

Because Lorraine repaid each loan, Wonga increased the amount it was willing to offer her each month. Just before she went into the repayment plan Wonga was offering to lend £700, but she said she would never have taken that amount as she knew she could not afford it.

(Osborne, “Wonga Borrowers Tell Their Stories: ‘I Had No Choice’”)

Here, the customer lied easily, without providing physical proof of income (requesting this is an uncommon practice across the board). Wonga, necessarily aware of such blatant asymmetric information in its approval process, still continued to increase its loan offer. It was ultimately up to the customer to determine the limit to her ability to pay. Dobbie and Skiba’s analysis of consumer behavior in the US loan market found evidence of significant adverse selection — in which one party has different or more accurate information than the other (280). With loan eligibility held constant, borrowers whochoosea $50 (approximately £40) larger loan were 16-44 percent more likely to default on the first loan, i.e. fall into rollover, repayment plans, or further loans. It’s conceivable that Wonga’s approval process allows customers to edge into a bracket that will put them into extended debt.

In the aftermath of Wonga’s collapse, a Financial Times article cited an anonymous person “with direct knowledge of the figures”, who said that the well-publicized low default rates were calculated on a per-loan basis, but “significantly more than half of customers eventually failed to repay, spiraling into debt as they took out new loans to pay off the earlier ones” (Megaw).

Predatory Collection Strategies

Default rates also present an illusion of a straightforward process to borrowers, as they do not take into account the role of continuous payment authority (CPA). Wonga, like many payday lenders, obtains permission through terms and conditions to automatically draw payment from user accounts when it is due. If the full amount is not available, smaller amounts may be withdrawn. FCA regulations later outlawed partial collection and limited lenders to two unsuccessful attempts before discussion with customers. The current Wonga.com site page explaining the role of CPA does not appear to have existed before 2015. Unless a CPA is canceled, default would reflect the borrower actually running out of money, without any further income to be pulled, and certainly after funds meant for rent, bills, or other subsistence have been drained.

CPAs, prior to regulation, have clear benefits of convenience through minimizing engagement, and they seemingly protect debtors from inadvertent late payments. Indeed, a single attempt to withdraw an amount, which is due to the creditor by contract, is not obviously wrong. Although the subsequent withdrawal attempts are also contractually agreed to, the unsoundness of that contract will be explored below. In addition, CPAs are the industry standard for UK’s online payday lenders, and therefore unavoidable to borrowers who have no alternatives to this loan. The lack of transparency means customers’ understanding of CPAs and their cancellation rights lags after the first withdrawals have been made. These are the same customers who are susceptible to additional difficulties from rent and bills that go unpaid because of an emptied account, sometimes taking out additional loans.

Other examples of Wonga’s aggressive solicitation tactics show the methods to be literally fraudulent. This refers to the letters sent to 45,000 customers from fictitious firms “Chainey, D’Amato & Shannon” and “Barker and Lowe Legal Recoveries” with, ironically, accusations of fraud and fabricated threats of legal action, despite a lack of evidence against the vast majority of these customers. The FCA upheld that this method of chasing delinquent loans was unacceptable (Patrick).

The Contractual Relationship

A previous analysis from the Seven Pillars Institute has pointed out that the goal of obtaining repeat clients creates incentive to break the initial loan agreement, and a contract meant to be broken is inherently unethical (Daniels). It has been demonstrated that Wonga and similar companies actively seek to pervert the contractual relationship through the above tactics. Kant’s formulations of the categorical imperative can be applied for a more rigorous analysis.

First Formulation: act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that should become a universal law without contradiction. (Kant)

Engineering a prevalence of continuous rollovers and ultimate defaults (as the high representative APR truly cannot be sustained as a genuine annual rate) would result in company losses and a need for its own line of credit to finance its loans. This is not necessarily possible or sustainable in a universally predatory and usurious environment.

Second Formulation: act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end but always at the same time as an end.

Third Formulation: therefore, every rational being must so act as if he were through his maxim a legislating member in the universal kingdom of ends. (Kant)

The improper contract means the borrowers are treated as means to an end rather than an end. By offering and entering into a contract that is not meant to be upheld, the lender does not treat the debtor as an autonomous person, since the debtor, as a rational, being, would not want to be knowingly in the broken contract. These formulations test whether “all rational beings should accept it regardless of whether they are agents or receivers of the actions” (Tan Bhala 16).

Justice and Fairness

We can further develop a deontological analysis through concepts of justice.

Aristotle considered justice to be the supreme virtue “because it is the sum of all virtues” (Tan Bhala 18). In the tradition of Aristotle, Thomas Acquinas identified two types of justice: commutative and distributive(Floyd). Commutative justice demands that business dealings ought to be conducted fairly such that a person is paid the value of his product. Both sides benefit equally from this fair transaction. Wonga and other payday lenders violate this through unfair strategies that drive prices which far exceed the value of their product and which the lenders were not prepared to pay. In case of default, the seller is not paid the cost of his service. In case of continual rollovers that eventually end with successful repayment, the seller has been paid the cost of his service (as in the original contracted loan) and much more, which is unfair to the buyer.

Distributive justice addresses the fair distribution of goods and responsibilities to people in a social community; here Aquinas believes that persons in high social standing deserve a greater portion of goods, but that there is a moral obligation to provide for the poor as well. This calls to the original conceptions of usury. John Rawls offers perhaps a more helpful principle of equality: “Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both (a) to the greatest benefit to the least advantaged and (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity” (Rawls 83).

In contrast, the proliferation of payday lenders in communities both indicates and intensifies economic distress. They do offer credit to otherwise deprived demographics or populations, with above-average composition of lower incomes, ethnic minorities, young adults, military personnel, etc.; at the same time, they penalize poverty through its methods of meeting, exploiting, and perpetuating that need (Gallmeyer and Roberts).

In this system, benefits are inversely proportional to the needs, but proportional to the means —lenders and the lenders’ funders possess means to generate revenue, and any wealthy borrower may in circumstances be able to benefit from the conveniences of payday lending, should they ever find themselves in these circumstances.

Because of this, Wonga’s behavior also fails a consequentialist analysis.South African co-founder Errol Damelin says he envisioned banking “independent of race, of gender, of class” with inspiration from his apartheid-era adolescence (Shaw). He conceptualized a lending entity that shunned human intervention in favor of data-centric tech solutions. Beyond Damelin’s societal vision, the tangible beneficiaries of Wonga and payday lenders include: consumers who actually match the textbook demographic, shareholders and owners, employees, and even the claims management companies that needed a new source of livelihood as the nation-wide payment protection insurance scandal came to a conclusion.

Yet the consumers do not match the demographic, as demonstrated. The shareholders and owners are in an uncertain position due to the direct consequences of its business practices; Wonga was ultimately stifled not necessarily by the FCA regulations, but by the redress claims that it was already accumulating. And ultimately, even if the company was morally inspired (in addition to business motivations, of course), it only superficially addresses the inequalities it helps widen.

Bibliography

Bar-Gill, Oren, and Elizabeth Warren. “Making Credit Safer.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 157.1 (2008): 1-101. Print.

Beddows, Sarah and Mick McAteer. “Payday lending: Fixing a Broken Market.” London: Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, 2014.

Bhutta, Neil. “Payday Loans and Consumer Financial Health.” Journal of Banking and Finance. 47 (2014): 230-242. Print.

Burgess, Kaya. “Church of England Quits Talks to Buy Wonga’s £400m Loan Book.” The Times, Times Newspapers Limited, 22 Sept. 2018, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/church-of-england-quits-talks-to-buy-wongas-400m-loan-book-h0m56nqzv.

Burke, Kathleen et al. CFPB. Washington, D.C.: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2014.

Charron-Chénier, Raphaël. “Payday Loans and Household Spending: How Access to Payday Lending Shapes the Racial Consumption Gap.” Social Science Research, vol. 76, Nov. 2018, pp. 40–54. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.08.004.

Creasy, Stella. “Legal Loan Sharks Are Circling the Poor | Stella Creasy.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 3 Feb. 2011, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/feb/03/legal-loan-sharks-regulating.

Dobbie, Will, and Paige Marta Skiba. “Information Asymmetries in Consumer Credit Markets: Evidence from Payday Lending.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 5, no. 4, 2013, pp. 256–282. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43189460.

De Bruin, Boudewijn, et al. “Philosophy of Money and Finance.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 14 Nov. 2018, plato.stanford.edu/entries/money-finance/#DeceFrau.

DeYoung, Robert and Ronnie J. Phillips. “Payday Loan Pricing,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Research Working Paper 09-07, Feb. 2009.

Ernst & Young. “The Cost of Providing Payday Loans in Canada.” Tax Policy Services Group Report, 2004.

Financial Conduct Authority. “FCA Confirms Price Cap Rules for Payday Lenders.” FCA, FCA, 11 Nov. 2014, www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/fca-confirms-price-cap-rules-payday-lenders.

Financial Ombudsman Service, Ltd. “Ombudsman Decisions.” Financial Ombudsman Service. https://www.ombudsman-decisions.org.uk/default.aspx

—. Payday Lending: Pieces of the Picture (Financial Ombudsman Service Insight Report). London: Financial Ombudsman Service, 2014. Web. 12 June 2019.

Floyd, Shawn. “Thomas Aquinas: Moral Philosophy.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, www.iep.utm.edu/aq-moral/#SH3d.

Francis, Karen E. “Rollover, Rollover: A Behavioral Law and Economics Analysis of the Payday-Loan Industry.” Texas Law Review, vol. 88, no. 3, Feb. 2010, pp. 611–638.

Gallmeyer, Alice, and Wade T. Roberts. “Payday Lenders and Economically Distressed Communities: a Spatial Analysis of Financial Predation.” The Social Science Journal. 46.3 (2009): 521-538. Print.

Goff, Sharlene. “Crisis Boosts Growth in Payday Loans Sector.” The Financial Times, Ltd., Financial Times, 6 Dec. 2011, www.ft.com/content/fc906960-2019-11e1-8462-00144feabdc0.

Jolly, Jasper. “Wonga Compensation Claimants May Lose Out Due to Automation Plan.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 4 Nov. 2018, www.theguardian.com/business/2018/nov/04/wonga-compensation-claimants-may-lose-out-due-to-automation-plan.

—. “Wonga Compensation Claims Rise Fourfold.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 12 Mar. 2019, www.theguardian.com/business/2019/mar/12/wonga-compensation-claims-rise-fourfold.

Johnston, Chris. “What’s Gone Wrong with Payday Lender Wonga?” BBC News, BBC, 27 Aug. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/business-45322061.

Jones, Rupert, and Patrick Collinson. “Archbishop’s Prayers Answered as Payday Loan Firms Brought to Book.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 20 Sept. 2016, www.theguardian.com/money/2016/sep/20/archbishops-criticism-payday-loans-causes-reform-industry.

Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Langley, Paul, et al. “Indebted Life and Money Culture: Payday Lending in the United Kingdom.” Economy & Society, vol. 48, no. 1, Feb. 2019, pp. 30–51. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/03085147.2018.1554371.

Laverty, Chris M. “Joint Administrators’ Progress Report for the Period 31 August 2018 to 27 February 2019.” London: WDFC UK Limited – in administration (the Company), 2019.

Mann, Ronald J, and Jim Hawkins. “Just Until Payday.” UCLA Law Review. 54.4 (2007): 855-912. Print.

Megaw, Nicholas. “Demise of Wonga Leaves Behind Concern for Vulnerable Borrowers.” The Financial Times, Ltd., Financial Times, 31 Aug. 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/231e9308-ad27-11e8-89a1-e5de165fa619.

Meyer, Harriet. “Wonga ‘Mr Sandman’ Ad Banned by Advertising Standards Authority.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 9 Oct. 2013, www.theguardian.com/money/2013/oct/09/wonga-ad-banned-payday-lender.

Murray-West, Rosie. “Wonga’s Interest Rate of 4,200pc? It’s Not an Automatic Red Card.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 19 Sept. 2011, www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/personalfinance/borrowing/8774054/Wongas-interest-rate-of-4200pc-Its-not-an-automatic-red-card.html.

Osborne, Hilary. “OFT Criticises Wonga Debt Collection Practices.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 22 May 2012, www.theguardian.com/money/2012/may/22/oft-criticises-wonga-debt-collection.

—. “Wonga Banned from Using Ad That Didn’t Mention 5,853% Interest Rate.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 Oct. 2014, www.theguardian.com/business/2014/oct/08/wonga-banned-tv-ad-interest-rate.

—. “Wonga Borrowers Tell Their Stories: ‘I Had No Choice’.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 10 Oct. 2014, www.theguardian.com/business/2014/oct/10/wonga-case-studies-credit-check.

—. “Wonga Increases Its Typical APR by 1,600%.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 21 June 2013, www.theguardian.com/money/2013/jun/21/wonga-increases-apr-1600.

Patrick, Margot. “U.K. Regulator Slaps Payday Lender Wonga.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 25 June 2014, www.wsj.com/articles/uk-payday-lender-wonga-fined-1403689249.

Poitras, Geoffrey. “3. Scholastic Analysis of Usury and Other Subjects.” The Early History of Financial Economics, 1478-1776: From Commercial Arithmetic to Life Annuities and Joint Stocks. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2000. Print.

Press Association. “Wonga Advert Banned for Implying 5,853% APR Was ‘Irrelevant’.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 Apr. 2014, www.theguardian.com/business/2014/apr/09/wonga-advert-banned-interest-rate.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978. Print.

Schwartz, M. S. and Robinson, C. 2018, A Corporate Social Responsibility Analysis of Payday Lending. Business and Society Review,123: 387– 413. doi: 10.1111/basr.12150

Shaw, William. “Cash Machine: Could Wonga Transform Personal Finance?” WIRED, Wired UK, 4 Oct. 2017, www.wired.co.uk/article/wonga.

Stabe, Martin, and Steve Bernard. “Payday Lenders’ Growth on Deprived High Streets.” Financial Times, The Financial Times, Ltd., 6 Dec. 2011, ig-legacy.ft.com/content/988eafda-2032-11e1-9878-00144feabdc0#axzz5rYDmydm8.

Stanley, Daniel. “Payday Lending: An Ethics Evaluation.” Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics, Seven Pillars Institute, 17 Oct. 2018, sevenpillarsinstitute.org/payday-lending-an-ethics-evaluation/.

Stegman, Michael A. and Robert Faris. “Payday Lending: A Business Model that Encourages Chronic Borrowing,” Economic Development Quarterly 17: 8-32, 2013.

Tan Bhala, Kara. “The Philosophical Foundations of Financial Ethics,” in Research Handbook on Law and Ethics in Banking and Finance, eds. Costanza A. Russo, Rosa M. Lastra and William Blair. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019.

Visser, Wayne A.M. and Alastair MacIntosh. “A Short Review of the Historical Critique of Usury.” Accounting, Business and Financial History, 1998, 8(2): 175–189. doi:10.1080/095852098330503

Wonga Group, Ltd. Response of Wonga Group Limited to the Competition Commission’s Statement of Issues of 14 August 2013. London: Wonga Group Limited, 2013. Web.